日本庭園と盆栽苑を巡るTraipsing around a Japanese Garden and Bonsai Exhibit

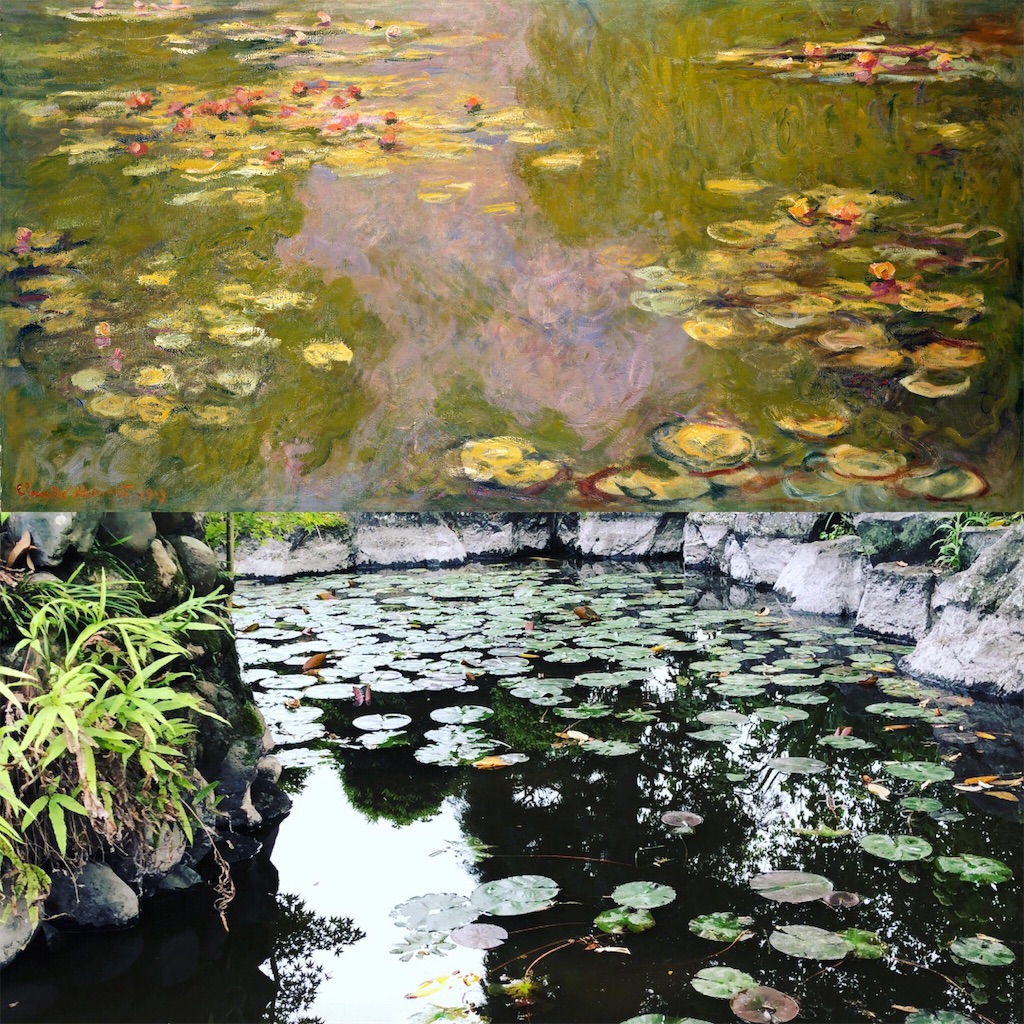

今週は休みを取って、日本庭園を見たい来日中のお馴染み友人を昭和記念公園 へ連れて行きました。拙僧は何回もそこへ訪れたこともありますが、公園の奥の方にある日本庭園まで足を運んだことはなかったので、拙僧は非常に楽しみにしていました。そこでは#盆栽苑 というところもあって、梅雨らしいの天候で誰もいなかったですが、そのしとしととした雨は敢えて憩いの効果もあって、すこぶる落ち着いた雰囲気を醸し出していました。また、樹の葉っぱに付着した雨の雫はその緑の度合い一層に鮮やかにして、まるでその色の光を放っていたようにも見えました。そこで働く庭師(らしい)方が #盆栽の基本、醍醐味、見方を詳しく説明して頂いたおかげで、今まで垣間見ることが出来なかった盆栽の小さい宇宙の中で繰り広げる偉大な世界観を堪能できました。

This week I had some time off to take lifelong friends from back home visiting Japan to Showa Kinen Park to see a Japanese garden, something they were eager to check out. I had visited that park many times before, but I had never ventured to the back to see the Japanese garden there, so I was also really excited to see it. They had a bonsai garden, and with the weather typical fare for the rainy season there was no one else there to enjoy it. The soft mist falling had a rather soothing effect, creating an extremely relaxing atmosphere. The drops of rain resting on the leaves of the trees made the hues of green even more vivid, as if they were giving off a green light of their own. We were approached by (what appeared to be) the gardener that worked there, and he provided us with an detailed explanation about the fundamental elements of #bonsai, their essence, and things to keep in mind when viewing them. Thanks to this great lesson, I was able to enjoy the worldview of the tiny universe that unfurls within each bonsai creation, something I was never able to do before.

盆栽は基本的にで三要素で成り立っています。(1) #根張り: 盆栽の根が四方八方に張り出して、安定感と力強さがあること。(2) #幹: 立ち上がりが素直で、上に行くほど自然に細かくなっていくこと。(3) #枝配り: 幹から出ている枝の太さや間隔がバランスよく配置されていること。これからの要素を兼ね備えたものが理想的とされています。盆栽の楽しみ方は人それぞれです。ある作品の一つは一人から見れば流れる滝に見える一方、また別の人から見れば上る煙や寄せる波にも見えます。何よりは、一つ一つの盆栽に大きいな自然の景色の広がりを感じることが盆栽の醍醐味であると言えます。

A bonsai creation is comprised of primarily three elements. (1) #Nehari: This refers to the roots spreading out in all directions from the base, creating a sense of both stability and strength. (2) #Miki: This describes the stem rising up unfettered, naturally growing smaller and more concise as it stretches higher. (3) #EdaKubari: This refers to the branches extending out from the main stem, with the varying thickness and space between them achieving a fine balance. The ideal bonsai tree features a combination of these three elements. The way in which each tree is viewed varies by person. In the eyes of one person, a bonsai tree can resemble a waterfall, while to another it resembles a plume of smoke rising or a wave lapping up on the shore. The most important thing is that each bonsai work delivers the essence of the art, which is simulating the grandeur of nature on a smaller scale.

数多くの作品の中から特に気に入ったものを挙げようとすると、幹の一部が白くなっている盆栽でしょう。樹齢300年の直幹という種類の一本の盆栽が非常に気になって、それは何故なのか最初わからなかったけど、庭師の説明を聞いてからその一本の盆栽の魅力とその作品に織り込めた演出がくっきり見えるようになりました。その白い部分は実は幹の枯れている部分であり、それを残すことで自然の厳しさを演出していると言われました。また、その枯れた幹の白色部分とと若々しい葉の緑色部分の美しい対照を際立たせ、「死」と「生」が表裏一体であることを表せ、栄枯盛衰その意味も体現しています。この諸行無常は日本の審美であります。

If I had to pick which type of bonsai I liked out of all the works on display, the pieces that really caught my eye were ones in which part of the stem was white. There was one piece of the "chokkan (straight stem)" variety that I liked a lot, and that tree was around 300 years old. At first I couldn't quite place why I liked that particular piece, but after listening to the gardener's explanation I was able to see the charm of this tree and form of expression imbued within it. According to the gardener, the white portion is actually the withered part of the trunk, and by leaving it within the piece the artist was able to convey the stark and severe face of nature. At the same time, the white portion of the trunk and the green of the fresh young leaves create a beautiful contrast, reminding us that "death" and "life" are inseparable. In short, this tree symbolizes the ebb and flow of life. That transience is the essence of the Japanese aesthetic.

印象派に窺える般若心経 Buddhist Undertones to Impressionism

ローグワンに窺える戦国武将 Samurai Traces in Rogue One

「フォースの覚醒」が公開された2015年はある意味で「スターウォーズの年」でもあって、世界中にそのワクワク感が繰り広げられました。この日本でも多岐に渡るスターウォーズ関連の企画が展開され、その一つは日刊スポーツが手掛けた「スターウォーズ新聞」でした。日本の独特のスポーツ新聞の形式を用いて、新作に関する情報を4号に渡って発信しました。2016年のローグワンの公開の前に日刊がその新聞を復刊して、数多くの興味深い記事も掲載しました。その記事の中で特に目に留まったのはローグワンのキャラクターを戦国武将に例えるものでした。完全に一致しないものもありますが、意外にも納得できる類似点が多いです。

The world was seized by a wave of excitement ahead of the release of The Force Awakens in 2015. In a certain respect, 2015 was “the Star Wars year.” Here in Japan, there were a number of Star Wars-related events and programs, one of which was the Star Wars Newspaper put out by the Japanese sports newspaper company Nikkan Sports. Four issues of the paper were released that year, with each issue introducing information about the new film through Japan’s own unique format for sports news periodicals. Nikkan Sports brought the paper back for a special issue in 2016 ahead of the release of Rogue One, and it featured a number of interesting articles. One that really caught my attention was a piece that paired Rogue One characters with famous warriors/warlords from the Sengoku (Warring States) Period that shared similar personality traits. Although some of the comparisons are a little off, it is interesting to see how many similarities there actually are. Here is my translation of the article.

帝国軍

Galactic Empire

ダースベイダー:徳川家康

Darth Vader→Tokugawa Ieyasu

強大な帝国軍の司令官として銀河に名を轟かすシスの暗黒卿。並外れたフォースを持つ若きジェダイ騎士だったが、ダークサイドに落ち、皇帝の右腕になった。

Dark Sith Lord and Supreme Commander of the Grand Imperial Army known all throughout the Galaxy. Once a young Jedi Knight with exceptional Force abilities who fell to the Dark Side and became the Emperor's enforcer.

家康的ポイント=フォース

Ieyasu trait: The Force

信長、秀吉の下で力を蓄えた虎視耽々。天下統一までの「最強のNo. 2」的立ち位置は家康ベイダー共通。人の弱点を見抜き人心掌握。洞察力はまさに「フォース」。

Ieyasu was a great warlord who built up his power under Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, waiting for his opportunity to seize control. The ultimate "No. 2" who ultimately unified Japan, Ieyasu's standing very much resembles that of Vader. His ability to see through people and identify their weaknesses resembles the perception one gains through the Force.

オーソンクレニック:本田正信

Orson Krennic→Honda Masanobu

デストルーパー部隊を率いる帝国軍の高階級将校。ダースベイダーの忠誠を装いながらも、陰で皇帝に取り入ろうと企んでいるらしい。

High ranking Imperial officer with his own squadron of Death Troopers. Feigns loyalty to Vader while attempting to scheme his way into the Emperor's graces.

正信的ポイント:嫌われ者

Masanobu trait: Loathed by all

家康の参謀として知略を尽くし県政をふるった。家康を裏切って敵対した過去があり仲間内から「腸(はらわた)の腐ったやつ」と嫌われた。嫌われ度はクレニック並みかも。

Staff officer to Ieyasu who used his intellect and wit to wield influence. Comrades who had once betrayed and fought against Ieyasu in the past claimed he was "rotten to the core." He may have been despised just as much as Krennic.

反乱軍

Rebel Alliance

ジンアーソ:真田幸村

Jyn Erso→ Sanada Yukimura

本作のヒロイン。有名な科学者の娘だが15歳の頃から1人で暮らす孤独なアウトロー。過去に犯した罪を帳消しにすべく、反乱軍に加入した。97.6%生還不可能なデススター設計図強奪計画に命を懸ける。

The heroine of this particular Star Wars tale. The daughter of a renowned scientist, she's a bit of an outlaw who has been on her own since the age of 15. Joins the Rebellion because she believes she needs to atone for her past sins. Ready to stake her life on a mission with only a 2.4% chance of success to steal the Death Star plans.

幸村的ポイント=強大な敵への超困難ミッション

Yukimura trait: Proclivity to tackle nearly impossible missions against imposing foes

九度山での孤独な幽閉生活から立ち上がり、大坂の陣で総数20万余徳川軍に挑んだ幸村。「何もかもなくしたゼロの状態→強大過ぎる敵に不可能に近い命掛懸けの戦い」という熱い運命がジンと重なる。「有名な父」という設定も似ている。

Yukimura began his life in solitary confinement on Mt. Kudo, and then went out with a bang in 1615 when he rose against Ieyasu and his grand army of 200,000 strong during the Osaka Castle summer campaign. Yukimura lost everything countless times in his life, yet always rose back up and gave his all to take on seemingly impossible odds. Jin's own life journey mirrors Yukimura's path and experience. Both of them also share the distinction of having a famous father.

キャシアンアンド―:直江兼続

Cassian Andor→Naoe Kanetsugu

ジンのお目付け役に任命され行動を共にし支える反乱軍の将校。実戦経験、情報戦ともに秀でるリーダー。自分でプログラミングしたK-2SOとは強い絆で結ばれている。

Rebel officer tasked with keeping an eye on Jyn and supporting their mission to find Galen. A true leader seasoned in combat and intelligence activities. Enjoys a tight bond with K-2SO, the Imperial droid he re-programmed.

兼続的ポイント=参謀

Kanetsugu trait: Strategist

上杉景勝を生涯にわたり支えた。外交を得意としあ資質も情報戦に秀でるキャシアンと重なる。石田光成と気脈を通じたと言われK-2SOとの関係に似ていなくもない。

Kanetsugu devoted his entire life to being the staunch rock for his lord Uesugi Kagekatsu. His outstanding acumen in diplomacy and counter-intelligence resemble those of Cassian. His rapport with Ishida Mitsunari also brings to mind the relationship Cassian shares with K-2SO.

K-2SO: 石田光成

K-2SO→Ishida Mitsunari

ジンたちに同行する警備ドロイド。帝国軍の監視ロボットだったかキャシアンが再プログラミング。瞬時に状況分析。自信家で独善的。C-3POと逆で人にかしずかない。

Security droid that accompanies Jyn and her "rogues" on their mission. Once a surveillance droid, he has been reprogrammed by Cassian to fight for the "good" guys. Able to analyze any situation nearly instantaneously, but a bit full of himself and self-righteous. The polar opposite to C-3PO, he doesn't wait on people.

光成的ポイント:分析力

Mitsunari trait: Analytical prowess

状況分析に優れた官僚として、秀吉政権を支えた光成。上にも下にも傲慢な態度をとったと言われ、人にかしずかない性格はK-2SOに似ているかも。

Mitsunari applied his superb ability to analyze any situation to support Toyotomi Hideyoshi's rule over Japan. Both his superiors and subordinates reportedly viewed him as haughty, and he was never one to wait on or cozy up to people. That seems to describe K-2SO to a "T".

ボーディールック:雑賀孫市

Bodhi Rook→Saika Magoichi

ある時は帝国軍の運び屋。ある時は反乱軍のエースパイロット。帝国軍のやり方に疑問を覚え反乱軍に加入。飛行技術は誰にも負けない。ひとたび操縦桿を握ればヒーローに。

Imperial cargo pilot one day, ace Rebel pilot the next. Decided to cast his lot with the Rebellion after doubting the methods and intentions of the Empire. Piloting abilities are second to none, transforming him into a hero the second he takes hold of the controls.

孫市的ポイント:芸

Magoichi trait: True specialist

無敵を誇った鉄砲隊を束ねる。報酬次第でどんな大名にも雇われるフットワーク。鉄砲という「一芸」を武器に信長を苦しめ、権力に屈しなかった。ボーディーと重なる。

Magoichi led a band of nearly invincible musketeers, willing to ply their trade for whichever warlord was willing to pay them the right price. A persistent thorn in Nobunaga's side with their deadly skill behind the trigger, never surrendering to any form of authority. Bodhi's character brings to mind these characteristics.

チアルートイムウェ:加藤清正

Chirrut Imwe→Kato Kiyomasa

ジェダイがほろんでしまった時代に、フォースの力を信じるスピリチュアルな盲目の僧侶。強じんな精神力で棒術の達人になった。明友ベイズと常に一緒にいる。

Fervent blind monk who continues to believe in the Force despite living in a post-Jedi galaxy. Drew upon his incredible spiritual power to become a master wielder of the bow staff. Always travels together with this trusted friend and ally Baze.

清正的ポイント=達人

Kiyomasa trait: Master warrior

秀吉豊臣下最強の武将。「七本槍」「虎退治 (文禄、慶長の役)」などで知られる槍の達人。築城の達人としても知られる。熱心な法華経信者でスピリチュアルなところもチアルートと共通する。

Kiyomasa was one of the most accomplished warriors to serve under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. One of the renowned "seven spearmen" and fierce tiger slayer (during the invasions of Korea in the 1590s). In addition to his skills in combat, he was also an expert castle architect. His fervent devotion and practice of the Lotus Sutra (Buddhism) reveals a devout spiritualism much akin to Chirrut's own faith in the Force.

注釈:初めてチアルートが一心に唱える「フォースは我と共にあり、我はフォースと共にある」と聞いたとき、すぐに思い浮かんだのは戦国時代の戦場で敵に襲い掛かるときにある仏教宗派の宗徒が唱えた念仏のことでした。それは浄土真宗から派生した一向宗という宗派であり、その宗派の総本山は現在の大阪府にあった本願寺でした。「南無阿弥陀仏」と唱え、仏に身を任せれば、戦死しても極楽土へと成仏すると信じていました。その念仏を意訳すると「南無阿弥陀は我の救済」という意味になります。この念仏の唱えはあまりにも滑らかであることから、繰り返して唱えると集中力を高めると同時に不安を一蹴する効果もあるという説もあります。その意味でこの南無阿弥陀仏の念仏はチアルートが唱える「フォースの祈り」と見事に連想するとも言えます。「南無阿弥陀から見ると皆は平等であり(無階級)」という宗教思想を布教する一向宗は、織田信長を始め当時の戦国大名がこの教団を強大を脅威と見ていました。

**Footnote: Chirrut's chanting of "I am one with the Force, and the Force is with me" instantly reminded me of a Buddhist chant from one sect that was commonly chanted by followers as they went into battle during this period. They were an offshoot of the Josdo-shin (True Pure Land) Buddhism, and their head temple was at Honganji (in present day Osaka). They believed that chanting "Namu Amida Butsu" would enable them to enter paradise should they perish in battle. One way to interpret this chant is "I take refuge in Amida Buddha". Some claim that the smooth manner in which the chant rolls off the tongue helps to remove anxiety and focus your concentration, so in that respect it is fitting that Chirrut mutters his own chant when entering the fray. Incidentally, rulers such as Nobunaga viewed this sect as extremely dangerous because they proclaimed all people were equal in the eyes of Amida Butsu (Amidtha Buddha), or literally "none above, none below".

ベイズマルバス:福島正則

Baze Malbus→Fukushima Masanori

相模で親友のチアルートのためなら命を惜しまない重装備兵士。後先を顧みない無鉄砲な性格。チアルートと対照的にスピリチュアルな力より巨大ブラスターを信じる。

Heavy weapons expert willing to lay down his life for his friend and sidekick Chirrut. A reckless character who doesn't think twice about the consequences of his actions. Not the spiritualist Chirrut is, he places his faith in the massive blaster he wields to deadly effect.

正則的ポイント=盟友

Masanori trait: Devoted ally

秀吉の小姓時代から加藤清正と仲が良く共に「賤ケ岳(しずがたけ)の七本槍」に数えられた。ベイズとチアルートの盟友関係と重なる。「無鉄砲な乱暴者」な逸話多数。これもベイズ的。

Masanori was another one of the "seven spearmen" under Hideyoshi at the Battle of Shizugatake against Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was close friends with Kato Kiyomasa, and both of them served Hideyoshi from a young age, displaying a strong bond that Baze and Chirrut mirror in the film. A reckless man that loved a fight, much like Baze in Rogue One.

ソウゲレラ:後藤又兵衛

Saw Gerrera→Goto Matabei

帝国軍の圧政の中でパルチザンを率いて権力に対抗する。その戦いぶりは過激で向こう見ず。あまりに苛烈なため見方からも恐れられる。

A leader of a partisan group that fights back against the oppressive rule and authority of the Empire. A rather extreme fighter that is sometimes more reckless than he is brave. His proclivity to go to the edge has made him feared even among allies.

又兵衛的ポイント=苛烈

Matabei trait: Hard core

戦国時代きっての猛将。大坂の陣で劣勢の豊臣方につき牢人達を率いて徳川勢に対抗。大軍勢に囲まれ壮絶に打ち死に。反権力と苛烈さがソウゲレラを想起。

Fierce warrior that lived through the thick of the Sengoku Period. Cast his lot with the outnumbered Toyotomi forces in the Osaka campaigns (1614-1615) and led a band of ronin (masterless samurai) against the Tokugawa army. Met a heroic death surrounded by enemy forces. His hard-core, borderline extreme resistance to authority conjures up images of Saw Gerrera.

日本の中空構造 Japan’s Functional Emptiness

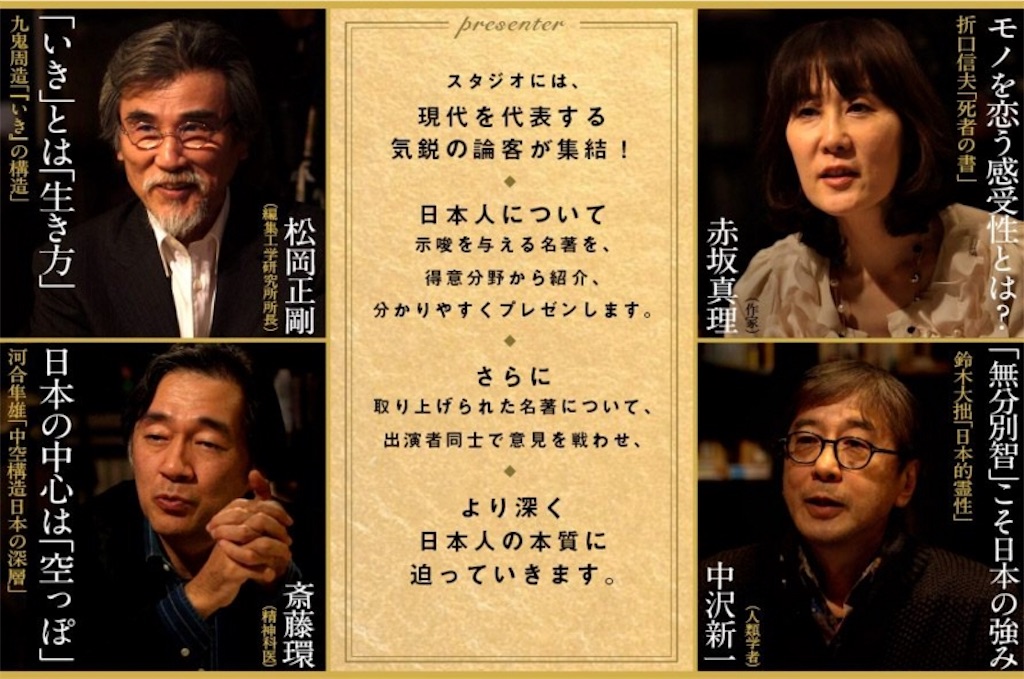

日本のテレビの気に入り番組を挙げようと言われますと、まず思い浮かぶのはNHKで放送される「100分で名著」です。「旧約聖書」から「般若心経」まで、多岐に渡る名著を取り上げて、四回(一回ずつは25分)に渡ってその名著のテーマと文化的な価値を考察する構造となっている番組です。ちょうど三年前の正月にこの番組のスペシャルバージョンである「100分de日本人論」が放送されて、非常に興味深い座談会となりました。この座談会に参加したのは現代日本を代表する下記の4人の論客:

If I was asked to name a particular Japanese TV program that I enjoy, the first one that comes to mind is “Master Works in 100 Minutes” on NHK. The show takes famous pieces of literature, ranging from works as diverse as the Old Testament and the Heart Sutra, and then examines their cultural importance over the course of four 25 minute episodes. Three years ago NHK aired a special edition of this program during the New Year’s Holiday. Dubbed “Japanese Theory in 100 Minutes”, this fascinating panel discussion brought together four of Japan’s leading scholars today:

Source: NHK

松岡正剛(編集工学研究所所長)

赤坂真理(作家)

中沢新一(人類学者)

Seigo Matsuoka (Head of Editorial Engineering Laboratory)

Tamaki Saito (Psychologist)

Mari Akasaka (Novelist)

Shinichi Nakasawa (Anthropologist)

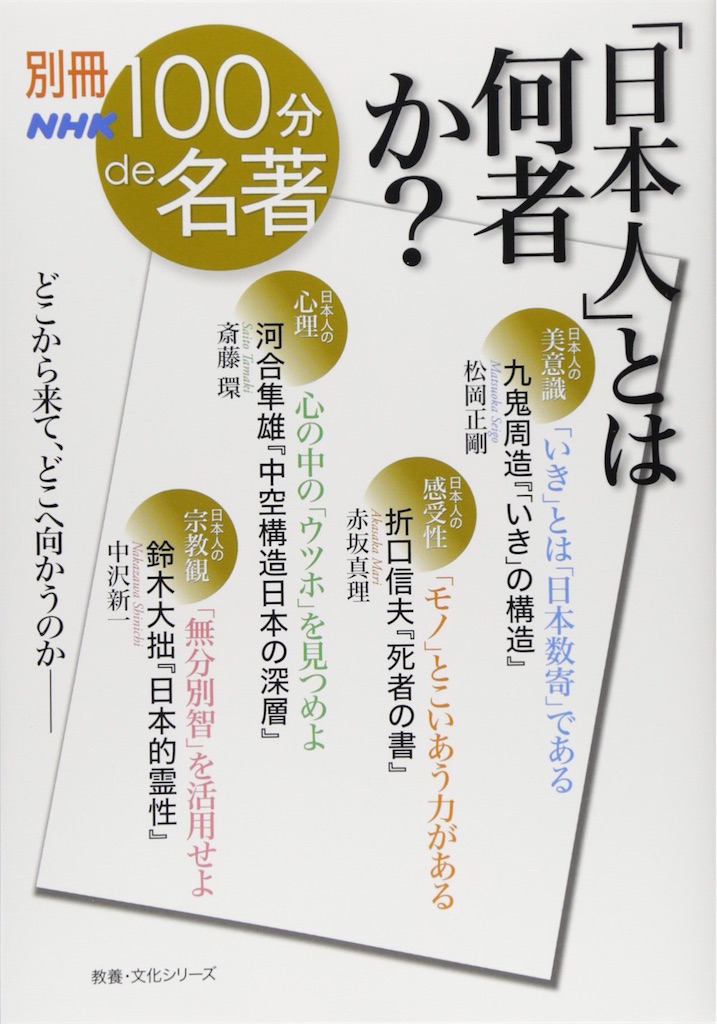

この四人が日本人の本質をよく表していると考える一冊を紹介し、分かりやすく解説するという特別企画でした。あまりにも深い話でもありましたので、座談会の内容をそのまま書き起こした出版物にもされました(購入済み)。

Each member of this panel discussion was asked to introduce and provide a straightforward explanation of one work they felt conveyed a unique Japanese quality. The conversation was incredibly deep, so much so that NHK decided to publish a volume that compiled everything the panelists said over the course of the discussion (a book which I have bought).

Getting to the Core of Being Japanese

このブログではこの座談会で紹介された本を一つずつ取り上げたいですが、まずこの投稿で考察するのは斎藤環が選んで紹介した河合隼雄(かわいはやお)の「中空構造日本の深層」の単著です。この本は「日本文化の中心は、空っぽなのだ」という長年の研究において河合氏が辿り着いた独特な持論が展開されます。

I’d love to examine each of the books discussed by this panel, but for the sake of this post I will take a look at the book introduced by Tamaki Saito: Getting to the Heart of Japan’s Empty Framework by Hayao Kawai. This book lays out the original theory that Kawai arrived at after many years of research. He argues that the core of Japanese culture is in essence “empty space”.

日本の神話には、正体不明の謎の神様というのが、必ず出てくると共通点に河合氏が注目を当てました。「それぞれの三神は日本神話体系のなかで画期的な時点に出現しており、その中心に無為の神を持つという、一貫した構造をもっていることがわかる。これは筆者(河合)が “古事記”神話における中空性と呼び、日本の神話の構造の最も基本的事実であると考えるのである。」

One common feature present throughout Japanese mythology that Kawai zooms in on is the presence of an obscure divinity. “In Japanese myths, we always see three divinities appear at key moments within the narrative. The central figure of these trinities is always an idle divinity that does nothing. I (Kawai) refer to this as the “emptiness” of the Kojiki lore, and it represents the most fundamental truth within all Japanese legends.”

Source: NHK

河合氏が取り上げる典型の例は古事記の冒頭に登場する三人の神:アメノミナカヌシ (天之御中主)、ツクヨミ (月読)、とホスセリ (火須勢理)。アメノミナカヌシとホスセリ (火須勢理)はちゃんと有為な神として扱われている一方、ツクヨミは何もしないです。河合氏がこの神話の構造をこう説明します:「日本神話の中心は空であり、無である。このことはそれ以後発展してきた日本人の思想、宗教、社会構造のプロトタイプとなっていると考えられる。」

In his book, Kawai calls attention to three divinities that appear at the beginning of The Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters): Amenominakanushi, Tsukuyomi, and Hoseseri. While Amenominakanushi and Hoseseri are depicted as active players in the narrative, Tsukuyomi does absolutely nothing. Kawai explains this mythological structure as follows: “The very core of Japanese myths is empty, indeed nothingness. This structure provided the prototype for the underlying make-up of all Japanese thought, religion, and society that have developed from that point (ancient times) forward.”

Source: NHK

この点について座談会の話が弾み出します。まず松岡氏が注目するのは「中心は空(うつ)である」である点です。以前この松岡氏が唱える「現(ウツツ)」が派生させる「移ろい」というコンセプトを考察する記事を書いたこともありますが、ここで松岡氏が同様のコンセプトが河合の唱える中空構造の仮説に置いて働いていると下記の通り解説します(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

This point really gets the discussion moving. Matsuoka’s draws attention to the “empty core” concept and states how the “空 (kuu, void or sky)” character in the word “中空 (chuukuu)” can also be read as “utsu.” This reading is derived from that of the character “現 (utsutsu, the now)”, which in turn gives rise to the idea of “移ろい (utsuroi, change or transition)”. I have explored this idea in a previous post, so check it out if you would like to learn more. As shown below, Matsuoka argues that this same concept is at work within Kawai’s “empty core” hypothesis (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

“中心に「ウツなるもの」を置き、それがあることによって両脇の二つが動いているという河合の仮説には納得のいくものがあります。一見空っぽだが、いざとなるとそこに何かが湧き出てきたり、力が潜んでいたりする。信号に青と赤のほかに黄色があるように、A/非Aという二尺せず、真ん中に三つ目を置くことによって、どちらも生かすのです。日本人は中空構造に無意識であるかゆえなのか、方法的なことをかなり特別に意識し、大切にしていると思います。そうしないと中空に異質なものが入ってきたときに、大変な事態になりかねない。”

“I believe there is some weight behind Kawai’s proposition of a three-part structure centered on something empty, but with that void putting the two sides into motion. At a glance it appears there is nothing but emptiness, but out of necessity this void can give rise to something, or transform into this well of latent power. A stoplight has not just red and green, but also yellow. It’s more than just A or not A; putting something in the middle allows us to keep both. Japanese people pay special attention to the processes behind things, perhaps because of this functional emptiness at work within their subconscious, and really cherish them. They have to clue in on these processes, for failure to do so can cause things to fall apart when something alien enters that void.”

中沢氏が松岡氏のいうこの中間の特徴が日本の社会や自然に対する価値観においてどのように機能しているか、そしてどのような危険性が潜んでいるのかを下記の通りの解説を付け加えます(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

Nakazawa further elaborates on this idea of putting something in the middle that Matsuoka described. In the following excerpt, he shows how this idea works within Japanese society and its view on nature, as well as the potential danger it entails (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

Source: NHK

“宇宙を作るには三項が必要だが、三項目は潜在的で表へ出ない。日本の神話において、天と地、海と山という二元論の起源はバーチャルで、このバーチャルに一項が与えられている、というのが河合さんの基本的な直観なのではないでしょうか。人間は、自然な状態だとこの思考方法が一番合理的で、例えば中空領域を置くことで、お互い妥協を図ることができます。自分と違うものを排除するのではなく、相手の原理を自分の中に入れることが可能になってくる。”

“You need three elements to form the cosmos, but the third is this latent force that never comes to the forefront. In my view, Kawai’s basic hunch is that an extra element is added to the virtual base underlying the dualistic facets of Japanese legends, such as the pairings of earth and sky or sea and mountain. This is the most logical mode of thought for human beings in our most natural element. In allotting this empty space, we create an area where we can work things out and reach a compromise with one another. Rather than simply eliminating what is different from you, it becomes possible to take the tenets of the “other” and make them a part of your being.”

“その例として典型的なのが、日本の風景は、中間領域を残しておくことが基本になっています。人間と、山の生き物。二つが重なり合うところに里山を作る。里山は中間領域ですから、人間にとっても、昆虫や魚、動物にとっても素晴らしい住処(すみか)にも成り得る。生き物の要求する生存条件を認めているわけです。計算や計画といった合理性で出来上がった世界には、中間がありません。ところが日本人の社会は中間性というものをベースにできていますので、その点は人類の期待、希望の星でもあります。しかしそのことに無自覚のままだと、70前の戦争と同じような状況に突入してしまう可能性もあるという、両刃(もろは)の剣でもあるのです。”

“Japanese landscapes provide us with great examples of this principle at work, for they are based on the idea of leaving some form of middle ground. This is the satoyama (里sato for “village” and 山yama for “mountain”) concept, or the idea of a place where human beings and life on the mountain come together. A satoyama holds the potential to be a truly wonderful place for all life—human beings, insects, fish, and animals—precisely because it is a middle ground. It’s an acknowledgement of all the conditions for subsistence that living things seek. On the other hand, there is no middle ground in a world rooted in the rationality of calculation and planning. In a certain respect, Japanese society stands as a beacon of hope for people of all humanity because it is based on this idea of allowing for room in the middle. That said, this very characteristic is a two-edged sword. If we are completely oblivious to this, we could fall headlong into the same set of circumstances as that war 70 years ago.”

そこから赤坂氏がその三項構造の考察を下記の通り続きます。中沢氏と同のようにこの三項構造は人間にとって一番自然な思考法と主張しつつ、過去に日本人がその構造に無自覚になるとどの悲惨を招いてしまうかを指摘します(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

Akasaka continues this examination of the three-part structure at work. Just like Nakazawa, she believes this is the most natural mode of thought for human beings. At the same time, she also draws attention to Japan’s past and the tragic consequences of becoming oblivious to this structure (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

Source: NHK

“日本人は「神」がわからない、世界で例外的な民族である」などというふうに、日本人自身の間でも、言われます。が、私は、この場合に「神」と言われている一神教の神という概念(そして善悪二元構造)は、危機の時代の思考の飛躍から生まれたものであって、人間の自然状態では「三項構造」を出してくるのではないかと思っています。この点は、中沢新一先生に確認しましたが、そうだということでした。”

“There are those who say—including some Japanese people—the fact we don’t understand “God” makes us one of the world’s unusual races. The God I’m referring to in this instance is of the monotheistic religious tradition based on a dualistic structure of good and evil. I’ve always held that this form of religion bursts forth from the intellectual currents of ages of crisis, and that the natural mode of thought for human beings is more aligned with a three part structure. Indeed, Professor Nakazawa has reaffirmed that is the case.”

“日本人が近現代まで、三項構造でやってこられたのなら、それは幸せなことだとも言えると思います。その三項構造の思考パターンを無意識に下敷きにして、天皇を神であり中心とした国を、明治(時代)に作りました。それはまさに天皇を「責任があって、責任がない立場」、つまり「三項構造の真ん中」のように中空構造につくるやり方でした。それは良い悪いではなく、ただの「構造」です。けれど、ただの構造であるからこそ、それが「利用」されるとき、誰にも止められず、誰の責任も問えない悲惨が発生します。それは入力したものが自動的に達成されるブラックボックスのようです。そして、そのことがうまく説明できなかったために、日本人は戦後、戦争のことについて口をつぐむことになりました。そして語れないひずみも、現在進行形でたまる一方です。あれほどの失敗は、まさに構造から来ていたと思います。そして、構造を用いるのにあまりに無自覚であったことから、来ていたと思います。その意味で思想的な「危機の時代」は、今も続いています。”

“Perhaps this three-part structure is what enabled Japanese people to endure into modernity. In that regard, I guess we could say we were blessed. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan created a nation state with the Emperor as the divine head in the center, a system unwittingly based on that very three-part structure mode of thought. This approach led to the creation of a system that placed the Emperor in a position of “both responsibility and no responsibility.” It was a reflection of this empty core concept. This is not a question of good or bad; in the end it is just a system. However, when this system is “used,” it can court disasters that no one can stop or take the blame for. It’s like this black box that automatically carries out whatever is put inside it. Japanese people were unable to effectively explain the nature of this system after the war, and this failure has caused us to remain silent on the issue. The strain wrought by this silence continues to pile up today. I believe the system is root of that grave mistake of the past. Indeed, the fact we were so oblivious to this system being used is what led to that mistake. In that sense, we still find ourselves in an intellectual ‘age of crisis’.”

Source: NHK

上記の三人が話したように、河合氏が唱える中空構造は柔軟性に長けた思考方法でありながら、一長一短もあり、それを自覚して上手くコントロールする必要があると斎藤氏が論じます。一方、外来のものというレッテルを張ったまま共存していくという長所があります。漢字はまさにその象徴です。「漢の字」が示すように、中国の字でもありながら、日本語に当てはまって1500年以上に使い続けられています。また、中空構造によって日本文化的なものを並行して温存されていくメリットもあります。かつての神仏習合はその典型的な例でしょう。朝鮮半島を通して日本に入ってきた大陸の宗教である仏教が道を排除することなく、妙な形で習合し、それぞれの宗教が欠ける点を補い合う日本の風土に適した独特な宗教の構造を醸し出しました。

Just as these three scholars explained, the empty-core structure described by Kawai is an incredible flexible method of thought. However, it is not without its faults. Saito argues that the important thing is to recognize both its merits and faults, and work to effectively manage them. One advantage of this system is that it incorporates elements from the outside, finds a way to make them coexist, yet also retain a vestige of their roots. We see this exemplified by the use of kanji in Japan. The very characters used to form the word 漢字 (kanji) make it clear where their roots lie. 漢 represents kan or han, which implies Chinese, and 字 for ji indicates written characters. While they were adapted to Japanese language and have been in use for over 1500 years, they’ve never lost that foreign label. Another merit of the empty-core structure is that it finds a way to preserve Japanese elements alongside those that enter from the outside. A classic example of this is 神仏習合 (shinbutsu-shuugo), or the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto. Buddhism entered Japan via the Korean peninsula. Instead of eliminating Shinto, Japan found a singular way to meld this continental religion with its own native beliefs, cultivating a unique system in which each religion made up for what the other lacked.

他方では、中空構造に潜む危険性に対して河合氏が警鐘を鳴らしたと斎藤氏が言います。その中心が空であることは、一面極めて不安であり、何かを中心に置きたくなるのも人間の心理傾向であると言えます。上記の赤坂氏の話でその傾向が招いた悲惨も触れました。河合氏も次の警告を残しました。「今度中心への侵入を許した場合、日本の中空構造はもはや機能しないのではないか。」河合氏の言葉を念頭に、日本人は全存在をかけた生き方から生み出されてきたものを、明確に把握してゆこうとしなければならいのはこの四人が至った結論です。これからの日本はこの教訓をどのように活かせるのかを拙僧も見守っていきたいと思います。

On the other hand, Saito shows how Kawai also warned of the danger inherent in this empty-core structure. The fact that there is nothing in the middle gives rise to a highly unstable quality. When faced with such instability, Kawai claims that human nature makes us want to put something in this middle ground. As we saw earlier, Akasaka touched upon the grave outcome of this tendency. Kawai leaves the following warning in his book: “The next time we let something encroach upon this middle space, Japan’s empty-core may very well cease to function.” With these words in mind, the four scholars concluded that the key is for all Japanese people to maintain a clear awareness of this structure, born of the living modus created over their entire existence. As we head into the future, I intend to see how Japan applies this lesson.

筆者の撮影

Author photo

喜捨(きしゃ)The Joy of Letting Go

スターウォーズエピソード4: 新たななる希望を始めて見たのはいつごろだったのかはっきり覚えていませんが、その映画が拙僧に焼き付けた印象は一生に渡って鮮明に映え続けています。印象的なシーンはあまりにも多いですが、その中で特に思いを寄せるのはルークにとって初めてフォースと触れ合ってその力を呼び寄せるシーンです。曹洞宗の僧侶である枡野俊明が著した「スターウォーズ 禅の教え」の前書きにはこのシーンを取り上げて、そこに窺える禅の教えを下記の通り解説します。

I don’t quite remember how old I was when I first saw Star Wars Episode 4: A New Hope. However, the indelible impression it left has remained vividly etched within my mind throughout my entire life. There are a number of memorable scenes in the movie, but one that I am particularly fond of is the scene in which Luke has his first experience with the Force and calls upon its power. The Buddhist priest Masuno Shunmyou (Soto sect of Zen) highlights this scene in the preface to his book Zen Wisdom from Star Wars, and provides the following discussion on the elements of Zen teaching it exhibits.

「一隻眼」を備える~智慧を持ち、一切の事物の本質を見る~

Unfettered eyes: The wisdom to see all things for what they are

禅の教えを読み解いた「スターウォーズ」エピソードIV、V、VIの中には、印象的なシーンがいくつもありました。中でもルークがオビ=ワンから初めてフォースの手ほどきを受ける場面は、「禅」と共通することが特徴的に現れています。ミレニアムファルコンの中でライトセーバーを使って修行を受けるルーク。そんなルークにオビ=ワンは、目隠し付きのヘルメットを渡し、「目は君を惑わすんだ。視覚を信じてはならん。」と、完全に視界を奪ってライトセーバーを使うよう教えます。これを見て私は「一隻眼」という禅語が思い浮かべました。

A number of scenes in the original Star Wars trilogy struck me in how they reflect Zen teachings. One that really left a deep impression on me was when Obi Wan gives Luke his first lesson in the ways of the Force. Watching that scene unfold, I felt that much of what Obi Wan says resonates with Zen concepts as we see Luke learn how to wield a lightsaber on the Millennium Falcon. Obi Wan hands him the helmet with the blast shield, effectively covering his eyes, and tells him “Your eyes can deceive you. Don’t trust them.” When I first saw this scene, the Zen word Isseki Gan (一隻眼) popped into my head.

Source: 田川悟郎書道 (Goro Tagawa Calligraphy)

仏教では、肉眼(通常の目)、天眼(未来を予知する目)、慧眼(一切の真理を見極める眼)、法眼(大宇宙の怒りに沿って真実を照らす眼)、仏眼(仏心で融通無碍に真実を照らす眼)の五つの真実を見抜く眼があるとしています。そして、「一隻眼」はこのすべてを兼ね備えており、智慧をもって一切の物事を見える特殊な能力のある眼(略)。オビ=ワンは、ルークに「一隻眼」を備えた人物になってほしいと願い、肉眼に惑わされないようにヘルメットをかぶせたのでしょう。ルークが「一隻眼」を備えた人物になり得たかどうか、「スターウォーズ」をご覧になっている皆さんにはお分かりのことだと思います。(以上)

Buddhism holds that there are five sets of eyes used to perceive the truths in Buddhism. First is the naked eyes (肉眼, niku-gen), which are used to see the world around us. Next we have the heavenly eyes (天眼, ten-gen). These eyes are for predicting what is to come. The third set is the wisdom eyes (慧眼, e-gen), which enable us to ascertain all forms of truth. The fourth is the dharma set of eyes (法眼, ho-gen). They shed light on the truth rooted in the reason underlying the macrocosms. Finally we have the Buddha eyes, which signify a merciful heart unhindered that illuminates the truth. That said, there is one set of eyes that encompasses these all. The Japanese word is一隻眼 (isseki-gan), and it describes possessing unfettered eyes with the special power to see all things by applying the wisdom we possess. I believe that Obi Wan was steering Luke in this direction, hoping that he would become a person endowed with unfettered eyes truly capable of seeing things (i.e. the Force) for what they really are. Thus, he covered Luke’s eyes with blast shield to ensure his sight would not cloud his view of the Force. For those of us who have seen the entire saga, we know how Luke ultimately did with this lesson. (End of quote)

さて、エピソード6が終わった時点でルークは本当に一隻眼が備えていたのでしょうか?最後のジェダイの展開を念頭に考えますと、その答えは「いや、まだ」と拙僧が思います。それはなぜかと言いますと、枡野僧侶が取り上げる上記のシーンに潜めているオビ=ワンの意図がヒントを与えます。では、上記の枡野僧侶の話の延長で仏教の基礎の知恵が網羅していると言われる般若心経のフィルターを加えて考察したいと思います。

Had Luke truly learned to look at the world (galaxy) with unfettered eyes by the end of Episode 6? Personally, I do not feel he had quite reached that point, given what we see unfold in The Last Jedi. I believe Obi-Wan’s intent within the scene that Masuno highlights above shows us why that is the case. Here I would like to expound upon the points Masuno raised by introducing an additional filter: the Heart Sutra, which is said to encompass all basic tenets of wisdom in Buddhism.

日テレの衝撃のスターウォーズ展 (From Nippon TV "Mind Blowing Star Wars Exhibit")

般若心経によりますと、私達が見るものは、経験に基づいて「心が決めているだけ」のものであり、そのもの実体はありません。私達は特定の概念を作り、その関連性の中で世界を見ています。この般若心経のフィルターを通して上記のシーンを改めて見ますと、オビ=ワンがルークに諭そうとしているのは概念に囚われずに世界(銀河)を見ることではないかと思います。ミレニアムファルコンの中でオビ=ワンの教訓を受けたルークが概念からの解放への第一歩を踏み出しました。だからこのシーンの最後にオビ=ワンがルークにこう言います:「より大きな世界(概念に狭まれず世界)に最初の一歩を踏み出したのだ」。

According to the Heart Sutra, all that we see is based on the definitions we create in our minds through our own experiences. These concepts have no actual substance. The relationships between the specified preconceptions we conjure form the framework by which we view the world. When we apply this Heart Sutra filter to the above scene, we see that Obi-Wan is trying to impress upon Luke the importance of viewing the world (galaxy) with eyes unclouded by preconceptions. Thanks to this lesson Obi-Wan imparts on the Millennium Falcon, Luke is able to take his first step towards freeing himself from preconceived notions. That’s why Obi-Wan says “You’ve taken your first step into a larger world (one unfettered by concepts)” at the end of this scene.

ただし、この大きな一歩を踏み出したものの、ルークは概念に囚われ続けます。まずはダゴバにてヨーダの下(もと)で修行を積むときのある失敗を経験します。フォースを使って沼に沈んだ己のX-Wingを浮かせて陸に移動するようにとヨーダに命じられ、やるのではなく「試みよう」とするルークは業が上手く運ばず、失敗に終わります。その失敗を招いたのはいうまでもなく概念でした。X-Wingのような大型の物体は機械を使わずフォースの力のみで浮かせて移動するのは無理(自分の経験から見て)と決めづけ、その結果自分に宿るフォースの力を阻む概念を作り上げてしまいました。ヨーダがフォースに信を置く手本を見せる目的はルークを諭すと同時に概念の無意味さを理解させるためでした。

However, even after taking his first major step into a larger world, Luke continues to cling to preconceptions. We see him encounter failure in his training with Yoda on Dagobah. Yoda tells him to use the Force to raise his sunken X-Wing from the swamp and move it to dry land. Luke “tries” instead of merely doing as he is told, and as a result he fails to complete the task handed to him. He convinces himself that that it is impossible (based on his own experience) to move a large object like an X-Wing using only the Force and not a machine. In short, he conjures up a preconception that inhibits the potential of the Force within him. In showing Luke what it means to put one’s trust in the Force, Yoda not only aims to admonish Luke, but also make him understand how pointless such preconceptions are.

伝説のジェダイ:ルークスカイウォーカー (Legendary Jedi: Luke Skywalker)

日テレの衝撃のスターウォーズ展 (From Nippon TV "Mind Blowing Star Wars Exhibit")

時を経た最後のジェダイのルークを見ると、この教訓はまだ完全に染み込んでいません。その逆に、新たに築き上げた概念に囚われています。それはダースベーダーの「伝説」とフォースの暗黒面の性質に対する概念です。ある意味で、その概念は師匠のヨーダが言い残したあの言葉から生み出されました:「一度暗黒の道にはまったら永遠に支配されてしまうぞ、お前の運命はな。」甥であるベンソロの中に繰り広げる闇を見たルークは、そこからのベンは永遠に暗黒面に支配され悪業と成してしまう運命(さだめ)が待っていると決めつけ、その「未来」を阻止するためベンを抹殺するしかないと考えました。自分自身が作り上げた概念が間違った行動を招いて、その結果ルークが阻止しようとした未来が現実となりました。

Luke still hasn’t fully learned this lesson by the time we see him in The Last Jedi. Rather, we find him held captive to a new concepts: his own preconceptions concerning the nature of the Dark Side of the Force and the legend of Darth Vader. In a certain respect, these ideas stemmed from the words that Yoda had uttered to him on Dagobah: “If once you start down the dark path, forever will it dominate your destiny.” When Luke saw the darkness spreading within his nephew Ben Solo, he assumed that it would forever dominate his path and destine him to commit horrific deeds. Thus, he decided the only way prevent this future from occurring was to murder him. This preconception that Luke built up within his mind led him to take the wrong course of action, which in turn ultimately brought about the very future he sought to avert.

最後のジェダイのアイマックスポスター (The Last Jedi Imax Poster)

その間違った行動に対する悔やみをあまりにも重く感じたルークは、フォースとの繋がりを遮断することにしました。そして、レイがアクトに来てフォースについて指導を求めても、彼女に宿る暗黒面を見てベンの二の舞が訪れるではないかと恐れたルークがジェダイの道に導くことを拒みました。レイが去る後にジェダイの遺産をぶっ壊すと決意したルークはちょうどそのときヨーダと再会します。そして、ヨーダと交わす会話で「概念は足枷であり、捨てるべし」と遂に理解します。枡野僧侶によりますと、禅に置いてこれは「喜捨」という表現が用いられています。「喜捨」はつまり「惜しむことなく喜んで捨てること」という意味です。喜捨の意味に悟ったルークはやっと「一隻眼」を取得し、オビ=ワンとヨーダが見せようとしたフォースの無限さを実感します。

The guilt of this mistake weighed so heavily on Luke that he decided to cut himself off from the Force. When Rey comes to Ahch-To in search of guidance in how to use the Force, Luke refuses to show her the ways of the Jedi because of the glimpses of darkness he sees within her. After Rey leaves, he decides to destroy the remnants of the Jedi order, and it is in this very moment he has reunion with Yoda. Speaking with his former master, Luke finally understands that preconceptions are nothing more than fetters that we must abandon. In his book on Zen and Star Wars, Priest Masuno describes this realization by using the Zen word “ki-sha (喜捨)”, which literally means “joyfully abandon regret”. When Luke accepts this notion of ki-sha, he obtains the unfettered eyes that allow him to experience the infinite potential of the Force that Obi Wan and Yoda attempted to show him.

喜捨。ヨーダがこの言葉の意味をよく分かっていました。だから最後に雷を落としてフォースの木を破壊します。「木(フォースの一面)を見て、森(フォースの全体)を見ず。」

Ki-sha (the joy of letting go). Yoda knew what that was all about. That’s why he summoned the lightning at the end to destroy the Force tree. You simply can’t see the forest (Force) for the trees (one aspect of the Force).

スターウォーズに反映される禅の考え方 Zen Thought Reflected in Star Wars

映画「スター・ウォーズ」の最新作、エピソード8「最後のジェダイ」の公開に伴って、毎日新聞が興味深い特集を掲載しました。「私とスター・ウォーズ」というテーマで、各界のファンにスターウォーズに対してどのような思いを寄せているかを語ってもらったという企画でした。その一人は禅僧の枡野俊明でした。彼は禅とスターウォーズの共通点は下記の通り語りました。

"The Last Jedi", the eighth installment in the Star Wars saga, is now out in theaters everywhere. The Japanese newspaper Mainichi Shinbun ran a special feature in which they asked people from different professions to talk about their own connection with the saga. One individual they spoke with was Masuno Shunmyou, a Zen priest. He described the connections he sees between Star Wars and Zen.

枡野俊明

Masuno Shunmyo

「スター・ウォーズは禅の影響を受けていると聞いたのですが本当ですか」。出版社の人にそう聞かれたのは数年前のことです。過去の作品を見ると、禅の考え方が反映されていることに驚かされました。人間の心をどう置き、どう世の中(銀河系の中)に向かっていけばよいのかを盛んに問いかけているように思えます。

A few years back a representative from a publishing company contacted me and said, “I’ve heard there are Zen influences in the Star Wars saga. Is that true?” I remember how surprised I was when I watched the original trilogy and noticed elements of Zen thought clearly reflected in the films. They are filled with scenes in which we see people grapple with how to set their mind and face the world (galaxy) in which they live.

この映画は、一言でいうと因縁の物語です。因とは物事の原因、縁とは人との関係や条件です。仏教には善因善果、悪因悪果という言葉があります。努力して良い原因を作っていくと、良い結果に結びつく。悪い原因を作ると、どんどん悪い方へ行く。同じ所から始まっても、一方は悪の権化であるダース・ベイダーのようになり、一方は、宇宙に平和をもたらすために戦う。因縁をどう結ぶかが非常に大切だと教えてくれます。

I believe the Star Wars saga can be succinctly described by the word in-en (因縁). The character 因 (in) represents the idea of “pretexts” that cause things to happen, while 縁 (en) refers to the connections and criteria by which we interact with others. In Buddhism we have the four character words 善因善果 (zen-in zen-ka) and 悪因悪果 (aku-in akka). Efforts to create good pretexts (善因) will ultimately lead to favorable outcomes (善果). On the other hand, sowing ill-intentioned pretexts (悪因) hasten your journey down the path of evil. The starting point is the same but the actions taken lead to different paths, as we see in Star Wars. There is Darth Vader, the embodiment of evil. We also have those who fight in order to bring peace to the galaxy. The Star Wars saga shows us why it matters how we choose to connect 因 (in, pretext) and 縁 (en, relationships).

人間はどう生きていくべきかを突き詰めているという点では、禅は哲学に近い。しかし、それを自分の体で実践して納得しようとするところに、禅と哲学の違いがある。だから、禅は「学ぶ」のではなく「行い」なのです。その「行」を修めることが修行。スター・ウォーズでは、神秘的な力であるフォースの使い手ジェダイになろうとする者が、学ぶのではなく、体得しようとする場面にも禅との共通性が見いだせます。

There is definitely a close affinity between Zen and philosophy, for both explore the question of how people are supposed to lead their lives. The key difference is that Zen stresses reaching understanding through physical experience. In that regard, Zen is more synonymous with “action” rather than “learning”. This action is cultivated through ascetic practice. We can see a similarity with wielders of that mysterious power known as the Force who strive to become Jedi in Star Wars. Instead of study, they seek understanding through experience (action).

今、禅に対する関心は、世界的に高まっています。これまで物質的な豊かさが、人間の豊かさや幸せを形成していると考えられてきました。でも、物があふれても決して豊かではない。それでは際限がないことに気づき始めた。禅は心の豊かさが一番大切で、物ではないと言い続けてきました。そこが着目されているようです。この映画の生みの親であるジョージ・ルーカス監督もまた、そうした生き方を作品を通して伝えてきた気がするのです。

Today more people around the world are taking an active interest in Zen. Throughout history people have put stock in material wealth as the basis for affluence and happiness. However, they find that an abundance of possessions does not make them rich, and begin to realize that this material wealth will never be enough. Zen stresses that it is spiritual wealth, not material, that matters most. People in this day and age are starting to clue into that. I believe that the father of the saga George Lucas was trying to show people this alternative approach to life through his Star Wars films.

ヨーダの教えに窺える東洋思想 Eastern Thought Underlying Yoda’s Teachings

''おまえと違ってわしにはフォースがついておる。強力な味方じゃ、それはな。生命がそれを生み出し、育てるのじゃ。そのエネルギーはわしらを取り囲み、結び付けておる。わしらは輝ける存在じゃ。粗雑な物質ではない。周囲のフォースを感じるのじゃ。ここにも、お前と儂の間にも、あの木にも、岩にも。どこにもある。そう、陸地とあの船の間にもじゃ。''

“And well you should not, for my ally is the Force. And a powerful ally it is. Life creates it, makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us. Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. You must feel the Force around you. Here, between you, me, the tree, the rock—everywhere. Yes, even between the land and the ship.”

スターウォーズのファンではなくても、ジェダイマスターであるヨーダのこの有名なセリフを聞いたことがある方は多いではないかと思います。フォースはあらゆるものに宿り、その力を意識して「受け入れる」ようにとルークを諭すときヨーダがこのセリフを言いますが、西洋国においてはこのヨーダがルークに授ける教訓はやや聖書めいた節になっていると言っても過言ではないと思います。このシーンではスターウォーズにおけるフォースという信義の基本的な思想はヨーダを通して説明されていますが、日本に来るまでその思想の「原点」についてあまり深く考えることはなかったです。でも、日本の文化と芸術に鮮明に反映されている宗教観を勉強するにつれて、その名言には東洋思想の影響が濃く映っていることに気づきました。

These famous lines are uttered by the Jedi master Yoda, and whether or not you’re a Star Wars fan, I’m sure many of you have heard this dialogue at some point. In the film, Yoda utters these words to Luke in attempt to get him to recognize the Force in all things and embrace its power. It’d be no exaggeration to say that this lesson Yoda imparts to Luke has taken on a Biblical status in Western countries today. Speaking through Yoda, this scene pretty much lays out the philosophy underlying the doctrine of the Force in Star Wars. I never really contemplated the origins of this philosophy before I came to Japan. However, as I studied the religious thought and worldview that is vividly reflected within Japanese culture and art, I came to realize the profound undertones of Eastern intellectual thought within the Force doctrine.

古代日本では「古神道」という信仰があって、それは現在の神社神道の礎ともなっている「自然崇拝」でした。そして、6-7世紀の間に主に渡来人の経由で仏教を始め、大陸の宗教が日本に伝導され植え付けられました。外来の宗教の「移植」によって当然なことに神道との「軋轢」が生じましたが、日本が選んだ道は「否定・除外」ではなく、「受け入れ・融合」のものでした。この道が生み出したのは日本の独特の神仏習合の宗教観でしたが、そのチャンプルーに「神(神道)」と「仏(仏教)」のほかに、「道教」という材料も混在していました。この記事の頭に述べたマスターヨーダの名言にはこの三つの宗教の思想が凝視されているではないかと思います。では、その一つずつの宗教とスターウォーズにおけるフォースという信義との関連を検証してみたいと思います。

The main religion of ancient Japan is referred to as “Old Shinto”, a system of beliefs centered around nature worship that formed the basis of present day “Shrine-based Shinto”. The 6-7th centuries saw the introduction of Buddhism and other religions from the continent via torai-jin, the Japanese term used to refer to immigrants from mainly the Korean peninsula. Naturally the introduction of these foreign-born religions gave rise to friction with Shinto, but Japan ultimately elected the path of accommodation and fusion rather than outright rejection and exclusion. This casserole of religions that came to coexist in Japan not only included Shinto and Buddhism, but also Taoism. I believe the quote by Master Yoda at the beginning of this post reflects elements of all three of these religions. Here I will take a look at each and how they relate to the doctrine of the Force in Star Wars.

まず、日本にて一番長い歴史を持つ神道から検証します。神道には「依代・憑代 (よりしろ)」という考え方があります。それは、あらゆる物に神・精霊や魂などのマナ(外来魂)が宿ると考える自然崇拝の宗教観の表れです。多くの神社の境内に見られる大きな神木がその考え方を象徴します。この神木は、榊や梛木(なぎ)のような革厚で光沢のある葉を持つ常緑の広葉樹であり、そこに神が降臨して依り憑くと信じられています。要するに、神聖かつ神秘的な力が宿るものを意味します。これはヨーダがいう自然なものに存在する(宿る)フォースのことと連想するではないかと思います。また、ジェダイ寺院の中庭に立派に聳え立つ「フォースの樹」のイメージも思い浮かべます。その名称の意味通りに、その樹にはフォースが宿り、まさに神道における依代との考え方に重ねます。

The first we have is Shinto, which is the oldest religion in Japan. One concept that is present in Shinto is the idea of yori-shiro. This concept is rooted in nature worship, and expresses the belief that supernatural power in the form of gods, spirits, or souls (collectively known as mana) can inhabit all things. The large sacred trees seen on the grounds of many shrines are a representation of this idea. Divinities are believed to descend and inhabit these trees, which are usually a type of flowering evergreen or Asian bayberry tree with thick bark and glossy leaves. That’s basically what yori-shiro is all about; the idea of a sacred and mystical power that dwells within things. This is seemingly reflected within what Master Yoda says when he describes how the Force exists (resides) within natural objects. Another image that comes to mind is the stately “Force Tree” that stood in the inner garden of the Jedi Temple. Just as the name implies, the Force was said to dwell within this tree, which coincides nicely with the Shinto concept of yori-shiro.

より東洋哲学的なフィルターを通してヨーダの名言を吟味しますと、道教の面影も窺えます。以前読んだことがあるブログにはこの点について詳しく解説されていますが、まずそこに載っている記事が指摘するのは「フォース」と道教における「気」の類似性という点です。道教は老子という古代中国の哲学者の思想に基づいて創立されたと言われていますが、老子の生涯にまつわる伝説と謎が多く、その詳細は歴然としません。これを念頭に置きつつ、その記事に下記の老子が言い残したとされている言葉を引用しています。

The vestiges of Daoism also become apparent when we apply the filter of Eastern philosophy to this famous quote of Yoda. This point is discussed to great length on a blog post that I have previously read. One thing the article points out is the striking resemblance between the notion of Ki within Daoism and the Force. Daoism supposedly emerged from the thought of Laozi, a philosopher in ancient China. However, much of Laozi’s life is enveloped by legend and mystery, and the truth is not much is known about him. Bearing that in mind, the article contains the following quote attributed to Laozi:

「道が之(気)を生み、徳が之を蓄え、物が之を形作り、勢いが之を成す。これにより万物において、徳を貴び、道を尊ばないものはない。道の尊、徳の貴は命ぜられることなく常に自然なればこそである。ゆえに道が之を生み、徳が之を見守り、之を伸ばし、之を育て、之を成し、之を熟し、之を養い、之を覆う。生み出しながら我がものとせず、成しながら功を誇らず、長じていながら仕切ることがない。これを「玄徳」という。」

“The way gives rise to Ki, virtue causes it to accumulate, objects give it form, and momentum generates it. Given this, all things under Heaven cherish virtue, with none forsaking the way. The respect for the way and loftiness of virtue are not preordained. They simply exist because they are naturally occurring. This is why the way gives rise to Ki, why virtue nourishes it, causes it to grow, nurtures it, encompasses it, refines it, cultivates it, and enshrouds it. Though virtue also emanates from within us, it is not ours to possess. While it underscores our deeds, we are not to boast of them. This virtue continually matures, yet never reaches full fruition. This is what we consider to be pure virtue.”

この老子(とされる)言葉を読んだとき、まず頭の中に浮かんだのは「生けるフォース」と「宇宙のフォース」の関連性でした。ミディ=クロリアンの故郷の星に訪れたヨーダに向けてフォースの女官達の一人である平静がフォースの在り様についてこう伝えた:「命は宇宙のフォースの力となり、宇宙のフォースは命を再生する」。この言葉はまさに上記の老子の「道が之を生み、徳が之を蓄え、物が之を形作り、勢いが之を成す」とよく似ています。ここで「道」と「徳」は用いられていますが、「道=徳」と読み替えることもできますし、日本語に置いては「virtue」という単語はその二つの字の組み合わせで成り立っています(道徳)。そして、上記の老子の言葉と挫折しているルークにヨーダが言う言葉を照らし合わせますと、その類似性が一目瞭然になります。「ゆえに道が之を生み、徳が之を見守り、之を伸ばし、之を育て、之を成し、之を熟し、之を養い、之を覆う」を再び読みますと、まるで反響のように「生命がそれを生み出し、育てるのじゃ。そのエネルギーはわしらを取り囲み、結び付けておる。」というセリフに連想します。

When I read this passage to attributed to Laozi, the first thing that came to mind was the relationship between the Living Force and the Cosmic Force. Serenity, one of the Force Priestesses, described the nature of the Force in the following manner to Yoda when he came to the home world of the midichlorians: “Life passes from the Living Force into the Cosmic Force and becomes one with it. One powers the other. One is renewed by the other." These words resemble what Laozi says in the passage above in describing the origins of Ki: “The way gives rise to Ki, virtue causes it to accumulate, objects give it form, and momentum generates it.” Here Laozi mentions both the way and virtue, but they are essentially referring to the same thing and can be interpreted as thus. Even more interesting is that the two kanji used to create the word “virtue” in Japanese, “道徳 (do-toku)” are the same as the characters used to refer to the way (道, do) and virtue (徳, toku). Now when we compare what Master Yoda says to a despondent Luke on Dagobah to the words of Laozi, we find a striking parallel. “Life creates it, makes it grow. Its energy surrounds us and binds us” seemingly echoes the interrelationship to which Laozi alludes: “the way gives rise to Ki… virtue nourishes it, causes it to grow… encompasses it… cultivates it, and enshrouds it.”

最後は仏教の面影です。あの名シーンの邦訳は非常に興味深い言葉が用いられて、その言葉は仏教に基づいた世界観を仄めかします。その言葉はヨーダがルークにいうセリフの最後に登場します:「ここにも、お前と儂の間にも、あの木にも、岩にも。どこにもある。そう、陸地とあの船の間にもじゃ。 」ここに注目が惹きつけるのは「間(あいだ)」というたった一文字で成り立つ言葉です。「間(あいだ)」を英語にしますと「space」や 「space between」という意味になりますが、その意味を成す別の読み方「ま」もあります。日本の歴史・文化・思想史を長年に渡って研究してきた松岡正剛はこの「間(ま)」という言葉の意味は歴史の流れに伴って変遷してきたと指摘します。“上代および古代初期においては、「間」は最初のうちは「あいだ」を指す言葉ではなかった。もともと「ま」という言葉は「真」という字があてられていた。「真」という言葉は、真剣とか真理とか真相とかというふうに使われるように、究極的な真なるものをさしていたのです。”

Finally we come to the visages of Buddhism within Yoda’s thoughts. The Japanese translation of that scene employs a pretty profound word that evokes a world view rooted in Buddhist thought. This word comes up in the final part of what Yoda says to Luke: “Koko ni mo, omae to washi no aida (間) ni mo, ano ki ni mo, iwa ni mo. Doko ni mo aru. Sou, rikuchi to ano fune no aida (間) ni mo ja (Here, between you, me, the tree, the rock—everywhere. Yes, even between the land and the ship).” The Japanese word that caught my attention consists of the single character read as aida (間). The word aida can be translated into English as “space” or “the space (between)”, but that same character can also be read as ma. Seigo Matsuoka—a scholar that has devoted his entire career to the study of Japanese history, culture, and intellectual thought—points out how the meaning of ma has changed over the course of history. “In ancient times and early antiquity the word ma (間) did not imply the meaning of aida (space, space between). Instead, the kanji character originally used for ma was 真. This character implies the meaning expressed in words such as 真剣 (“shinken”, or “earnest, solemn, sincere”), 真理 (“shinri”, or “(a) truth), and 真相 (“shinso”, or “(the) truth''). In short, the word ma conveyed the idea of some ultimate truth.”

仏教においてその究極的な真なるものを挙げますと般若心経が唱える「色即是空」という真理です。つまり、この世界は「空(くう)」であるとのことです。この「空(くう)」を直訳しますと「empty」や「void」となりますが、なんかいまいちの訳になり、それで空が指す意味がなかなか訳出されないと拙僧が思います。この文脈において空が指すのは「概念」であり、その概念がないことを理解しますと見方が180度転換します。つまり、我が見るすべてが実態を持たない「概念」に過ぎず、その概念から解かれるとこの世界は常に移ろいでいることに気づきます。これはまさにヨーダがいう「You must unlearn what you have learned (今まで学んできたことを念頭から払う必要がある)」のことです。陸地とX-wingの間は「空」でもありますが、そこにフォースが常に移ろいでいて、流れています。その流れには形は無い、だからそのフォースに対して概念に囚われて見てはいけないとヨーダがルークに諭そうとしています。遂にルークがその真理に悟りますと、繰り広げる空(そら)の如くフォースの無限さを理解できて、その時まで足枷となっていた概念から解放されます。

The ultimate truth within Buddhism is expressed by the four kanji construct in the Heart Sutra: “色即是空 (shiki soku ze kuu, or “all form is emptiness”). The last character of this construct, 空 (kuu), implies that all things in this world are without form. This is a tricky character to translate into English, for a literal translation churns out words like “empty” and “void”, both of which fail to fully convey the idea of kuu. The word kuu in this context is used in reference to “concepts” or “ideas”, and the fact that we must realize they do not exist. Once we understand this, we can see the world in an entirely different light. In short, everything that we see is nothing more than “concepts” that have no substance or entity. When we break free from these concepts, we come to see that the world is transitory, in a state of constant change. This liberation from concepts is what Yoda means when he tells Luke that “you must unlearn what you have learned.” The space between the X-wing and the shore may be just that… nothing but open space. However, therein flows the Force, and it is transitory in nature. That flow has no form, which is what Yoda admonishes Luke to realize. One must not look at the Force while still held captive to concepts. Luke eventually arrives at this truth and comes to understand that much like the sky that spreads overhead, the Force is equally expansive and unbound. This realization frees him from the shackles of concepts that had previously stifled his understanding.

スターウォーズの宇宙観を生み出したルーカス氏がこのヨーダの名言に敢えてこの深遠な意味を込めたかを立証するのは難しいが、視点を変えて違うフィルターを通してスターウォーズを見ると、新たな発見が窺えてきます。それはこの物語が文化を超越する普遍性が潜在している証ではないかと拙僧が思い、また何度もスターウォーズを見て考察する醍醐味はそこにあると思います。

Admittedly, it is difficult to ascertain whether Lucas himself infused this depth of meaning within this cosmic saga that he created. That said, new discoveries await those who change their vantage point when examining Star Wars. I believe this is a testament to the universality inherent within the Star Wars saga, and what makes repeat viewings of the films all the more worthwhile.