Kage and Ohigan: Two Points of Reference in Viewing Ahsoka Series Episode 5 「影」と「お彼岸」を基点に見るアソーカシリーズのエピソード五

いつものように、新しいスターウオーズを見るとき、まず英語音声、日本語字幕で見て、その後は日本語吹替で観る。 #アソーカ シリーズの視聴もそうであった。日本語吹替で観るときは、その日本フィルターを通して新たなスターウオーズの面を垣間見える。アソーカの第五話の「影武者」のエピソードでも、またこういう発見もあった。

I always watch new Star Wars in English with Japanese subtitles first, and then do my repeat viewing in the Japanese dub. The Ahsoka series was no different. Watching Star Wars in the Japanese dub helps bring to light new facets of Star Wars brought into focus by that Japan filter. Episode 5 of the Ahsoka series, "Shadow Warrior", once again brought new discoveries.

Source: Disney

そのタイトルの日本語訳を見た瞬間に集中が一旦途切れてしまった。「影武者」?英語のタイトルは「#ShadowWarrior」となる。拙者の母国語は英語であるから、まず思い浮かんだのは「陰に潜む武者」や「幻・幻影の武者」というイメージ。一方、日本語の「影武者」はやや違う印象を与える。最初に連想したのは、#黒澤明監督 の作品である #影武者。

My concentration broke for a split second when I first saw the Japanese title. #Kagemusha? The English title is #ShadowWarrior. To me this initially suggested "a warrior lurking in the shadows" or "an apparition of a warrior". However, the Japanese title "Kagemusha" conjures up different images. The first that came to mind was what is seen in the #AkiraKurosawa film #Kagemusha.

Source: Toho

戦国時代において、大名達は敵の目を欺くために、同じ服装をさせた身代わりの武者を起用した。黒澤監督作品の「影武者」では、武田信玄が急逝したあと、敵の目を欺くためその影武者が信玄に「なりきる」。でも、「影武者」という日本語にもう一つの意味がある。国語辞典によると、影武者のもう一つの意味はこう:「 陰にあって、表面にいる人の働きを助ける人。または、表面の人を操る人。黒幕。」さて、この #アソーカ の第五話のタイトルにおいて、どの意味が働いているであろう。

Daimyo in Warring States Japan often used doubles to protect themselves from enemies. In Kurosawa's film, we see the "kagemusha" of Takeda Shingen essentially become him after Shingen's sudden death. But that is not the only way kagemusha is used in Japanese. The Japanese dictionary has this definition as well: "Someone in the shadows helping the person in the light. Someone behind the scenes controlling that person." Reading that definition made me think about which part the Japanese title could be hinting at for Episode 5 of Ahsoka.

この #アソーカ の第五話では、「 陰にあって、表面にいる人の働きを助ける人」という意味合いが働いているとも解釈できよう。「表面にいる人」はアソーカであり、その人の動きを助ける人は「#アナキン の幽霊」。精神的にアソーカが停滞していた、アナキンとの再会によりそれを脱することが出来た。ここでこの「影武者」の「影」の字を考察したい。この字が好きだ。数多くの日本語の単語に用いている。その中に挙げたいのは「影響」と「面影」との熟語。まず「影響」。字ごとに分解するとすごい意味になる:「影が響く」。フォースを通して、代々のジェダイの「影」が響き渡ると言うイメージ。

One take could be the first part: ""Someone in the shadows helping the person in the light." The person in the light is Ahsoka, and the person helping her is #Anakin's ghost. Ahsoka had mentally stalled, but thanks to this reunion with Anakin she overcame that. Here I want to look at the 影 (kage) character in 影武者 (kagemusha). I love this character, and it's used in lots of Japanese words. Two of these are 影響 (eikyo) and 面影 (omokage). First we'll look at 影響 (eikyo). When you break it down, you literally get "kage ga hibiku (the echoing of the shadow)". This conjures up the idea of the "kage" of past Jedi echoing through the Force to those Jedi in the present.

アソーカにとってフォースの中で一番輝かしい「影」は当然アナキンである。アナキンの影が絶えずに響いて、アソーカに影響を与え続けている。「影の武者」は絶大な影響を誇る師匠であり、フォースを通してアソーカはマスターのinfluence (影響)を受けてる。こう「影」の解釈がなかなかいい。次は「面影」。これまたすごい単語。字を分解すると「面(表)にある影」となる。「面影」は記憶の中に宿って、つまり思い出である。アソーカの場合は記憶の中にアナキンの面影があり、彼の影(影響)がアソーカの表(行動)に現れる。この第五話がまさにそれを描写した。

For Ahsoka, the brightest "kage" in the Force was naturally Anakin. His "kage" never stopped echoing, always influencing Ahsoka. The presence of this "kage no musha (shadow warrior)" was immense, and Ahsoka felt that presence in the Force. I like this take on the meaning of "kage". Next we have 面影 (omokage), a truly amazing word. Breaking it down character by character we get "omote ni aru kage", or "shadow on the exterior/outside". "Omokage" refers to something lurking in the conscious, essentially a memory. Going with this line of thought, we see that Anakin is the omokage present within Ahsoka's mind and memories. His "kage (ei-kyo; influence)" can be seen in the outward expression (actions) taken by Ahsoka. Episode 5 can viewed as a depiction of this.

Shadow Warriorを「影武者」と訳出するのは直訳すぎとは最初の印象であったけど、この語彙と字ごとをこうやって考察していくうちに、思ったより深い意味がそこにある。翻訳者がそこまで考えたかわからないけど、この考察を経て自分也の納得に辿り着いた。やはり日本語がスターウオーズに合う。

As I said, my initial reaction was #Kagemusha was too literal a translation of #ShadowWarrior. But in taking a closer work at the word, it became much deeper. I don't know if the translator had that in mind, but this word exercise proved useful for me, and reminded me again of what a great match Star Wars and Japanese are.

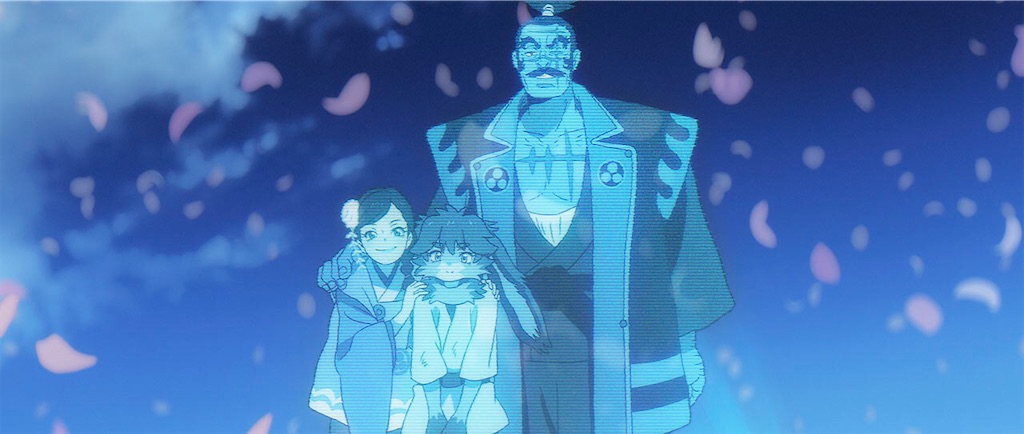

「影武者」のエピソードでアソーカとアナキンの再会の舞台となるのは「狭間の世界」というところである。このエピソードが最初に配信されたのは9月の中旬であって、ちょうど「お彼岸」との時季と重なった。「お彼岸」は日本の仏教の用語で、春分、秋分の日を真ん中にしたそれぞれ七日間を指す。しかし、哲学者である門脇健によるとなぜ春分や秋分の日の前後が「お彼岸」とされるのかはあまりはっきりしていない。『文藝春秋』2013年4月号では門脇氏がこう解説した。

The stage for Anakin's reunion with Ahsoka in Episode 5 ''Shadow Warrior'' is known as the ''World Between Worlds''. This episode was first aired in mid-September, which happens to coincide with the ''Ohigan'' season in Japan. "Ohigan" is a Japanese Buddhist term that describes the seven day period around the start of spring and fall. Japanese philosopher Ken Kadowaki says it's not really clear why that is the case. He provided this explanation in the April 2013 edition of the magazine Bungeishunshu:

「お彼岸」は、インドや中国、朝鮮半島には見られない日本独自のものらしい。おそらく、夕日や夕焼けに対する日本土着の独特の感性と西方浄土の阿弥陀仏への信仰が重なって、このような習俗が形成されたのであろう。つまり、春分・秋分の前後の真西に沈む夕日に西方浄土の方角を確認するとともに、その浄土で阿弥陀仏に迎え入れられた故人を偲ぶと観念されるようになったのである。また、沈む夕日に自分自身のいのちの終わりをも重ね合わせ、いつしか阿弥陀さまや先に逝かれた親しい人々に「ご苦労さまでした」と迎えられる日を想うのである。」

"Ohigan seems to be unique to Japan, with no equivalent really seen in Indian, Chinese, and Korean Buddhism. Japan has always had an affinity for sunset and the setting sun, and this seems to have melded with the worship of Amida (Amitābha), the Buddhist deity residing in the western paradise. Basically, people in Japan came to view the setting sun in the west on the two equinoxes as means to confirm where that western paradise may lay, and thereby think of cherished ones who had crossed over to be welcomed by Amida. In addition, the setting sun on these days brought to mind their own fleeting mortality, making them think of the day when they too would be welcomed by Amida and those dear to them with a heartfelt "well done". "

Source: Author photo

「その浄土で阿弥陀仏に迎え入れられた故人を偲ぶ」を読んだ時、アーソカシリーズの第五話の #影武者が思い浮かんだ。既に浄土(=宇宙のフォース)で阿弥陀仏 (=アミダラ=パドメ)に迎え入れた師匠であったアナキンを偲ぶアーソカは、狭間の世界でアナキンと再会、新たな教訓を授かる。門脇氏の解説を念頭に改めて見ると、お彼岸に狭間の世界を見出せる。またお彼岸のころは、赤い花火の如く華が咲き乱れる。この時季に見られるから、日本では「彼岸花」という呼称が付けらている。極楽浄土から舞い戻った故人のように、アソーカに自分の姿を現すとき宇宙のフォースから生けるフォースに還ったアナキンの輝かしい存在をよく表していると思う。

#お彼岸 #アーソカ #アナキンスカイウォーカー #宇宙のフォース #生けるフォース #彼岸花

When I read the "think of cherised ones who had crossed over..." part, I thought of what we see play out in Episode 5 in the Ahsoka series. Ahsoka's thoughts go to Anakin, who has already crossed over to paradise (i.e., cosmic Force) to be welcomed by Amida (=Amidala=Padme). She then meets him in the World Between Worlds, where he imparts a new lesson. In a certain sense, there is a parallel between the World Between Worlds and Ohigan when rewatching this episode with Professor Kadowaki's explanation in mind. Likewise, there is a certain flower resembling a red firework burst that blooms around the time of Ohigan here in Japan. While it is known as a "spider lily" in English, in Japanese it is called "Higanbana (bana=hana=flower)". Just as cherished ones who crossed over to paradise come back at this time of year, I feel these bright flowers are a nice analogy for the bright presence of Anakin going from the Cosmic Force back to the Living Force when he shows himself to Ahsoka. #Ohigan #Ahsoka #AnakinSkywalker #CosmicForce #LivingForce #HiganBana

Source: Photos by author

「スターウオーズビジョンズ:村の花嫁」に窺える日本の中空構造とフォースの生かし方 Japan’s Functional Emptiness and Channeling the Force in Star Wars Visions: The Village Bride

アニメとスターウオーズのファンにとって「スターウオーズビジョンズ」は夢に見た企画と言っても過言ではない。スターウオーズの世界観の礎の一部ともなっている日本文化だけど、スターウオーズビジョンズはこの原点が前面に出ているだけではく、日本アニメという媒体を通して斬新なスターウオーズを見させてくれる。それぞれの短偏は個性に富んでおり、そこに日本のらしさも漲っている。どれも完成度の高い作品だけど、拙者の心に一番響いたのはキネマシトラスの「村の花嫁」だった。

It would be no exaggeration to say that Star Wars Visions was a dream come true to fans of both Star Wars and anime. Japanese culture is one facet that lies at the heart of “Star Warsiness.” Star Wars Visions not only brings these Japanese origins to the forefront, but uses the medium of Japanese anime to show us a fresh new take on the Star Wars universe. Each short is brimming with both originality and uniquely Japanese elements, making for self-contained works. However, the one that really resonated with me was “The Village Bride” by Cinema Citrus.

Source: Disney, Cinema Citrus

この短編の舞台となっているのは自然の豊な惑星にある村だ。初めて見たときにすぐに思い浮かんだのはこの東京の西多摩地方と山梨の県境に連なって森林に覆われている山岳地帯であった。キネマシトラスがまさにそれを表現しようとした。そして、この惑星はフォースを掘り下げるキャンバスともなる。塀和(はが)等監督はこう説明する:「周囲の森や自然と一体化したこの村は、日本の山岳地帯が基となっています。中部山岳地帯、とりわけ北アルプスや立山連峰を参考にしました。そこに根付く文化と、様々な儀式や宗派で山を祀る伝統を表現にしたいと思ったんです。村人は自然を敬っている。その気風のなかにフォースと相通ずるものがあるじゃないかと感じました... 私はこの作品で、フォースとは何かを描きたかった。"スターウオーズ"の世界観を保ちつつ、フォースの本質を掘り下げたと思ったんです… "スターウオーズ"という枠内に収めつつも、今まで描かれなかった形でフォースとは何かを表現すること。それが目標でした。映画しか知らない人たちは新しい要素を見せられる"中間地点"のようなものを探ったんです」(出所:スターウオーズ:ビジョンズ 公式アートブック)

The stage for this anime short is a village on a planet teeming with natural life. When I first saw “The Village Bride”, I instantly thought of the wooded mountains here in western Tama (Tokyo) and the border of neighboring Yamanashi prefecture. Indeed, that was the kind of natural vista that Cinema Citrus sought to portray, according to director Hitoshi Haga. This planet also served as the canvas for a deeper exploration of the Force. “The village that serves as the stage for this tale is a part of the forest and nature around it. The underlying inspiration here was the mountainous ranges found throughout Japan, with special reference to the Northern Japanese Alps and Tateyama Renpo area (central part of main island Honshu). I wanted to take elements of the culture, various rituals, and religious practices that worship the mountains and put them within Star Wars. The village inhabitants revere nature. I felt that within this reverence we could find something akin to the Force…I wanted to portray what the Force is through this anime short. Indeed, the idea was to dig deeper into the nature of the Force while preserving the elements that make Star Wars what it is… Operating within those Star Wars parameters, I wanted to show a side of the Force that has not been depicted. That was our goal with The Village Bride. In a way, this short depicts a ‘middle ground’ that shows something new to people who only know the Star Wars films.” (Source: The Art of Star Wars Visions)

御岳山 (東京都)の頂点からの見晴らし (記者の撮影)

View from top of Mt. Mitake in Tokyo (photo by author)

この短編で描かれる村人はフォースを「マギナ」と呼んでいる。このマギナの紹介は印象的であった。結婚式の前日に、修験道の如く山道を進む若い新郎のアスが籠搭乗の新婦のハルを背負って、どんどん山を登っていく。二人は神秘的な巨大な岩の前に辿り着き、それに向けてマギナに祈りを捧げる。二人そろって、この祈りをマギナに捧げる:

The villagers depicted in this anime short refer to the Force as “Magina.” The way in which the storytellers introduce us to this idea of Magina is quite striking. We see the young groom Asu carrying his bride Haru in a chair on his back, ascending a mountain path akin to those traversed by itinerant Buddhist priests doing their mountaineering ascetic practices in medieval Japan. The two come before a large boulder, and then offer up this prayer to Magina.

ハル:「我らは空、我らは森、我らは川」

Haru: “We are the sky, we are the forest, we are the river.”

アス:「我らは山、我らは雲、我らは風」

Asu: “We are the mountain, we are the cloud, we are the wind.”

ハルとアス:「我らは一つ。マギナよ、立ち昇りたまえ。」

Haru and Asu: “We are one. Magina, may you rise.”

*英語の吹替だと「我らは空、我らは森、我らは川」は二回繰り返すけど、日本語の音声は「我らは山、我らは雲、我らは風」に続く。ここで敢えて日本語の字幕を引用し、英訳を付け加えた。

*While the English dub repeats the line “We are the sky, we are the forest, we are the river,” the Japanese dub continues with what translates to “We are the mountain, we are the cloud, we are the wind.”

Source: StarWars.com

アスとハルはその高台から地平線まで繰り広げられる景色に目を配る。まず、最初に見るのは幼いころの二人の共通の記憶のようである。友達と川で遊んで、石を並ばせてその流れの方向を変えて魚を誘導させようとする。そして、次の瞬間、マギナの力で地面が亀裂し、山が崩れて川の流れも激しく変わる。おそらく二人が見たのはこの惑星に宿るマギナの記憶であろう。我ら観客と同じ目線でこの二人の婚約者を追ってきたのはこの短編の主人公である元ジェダイの “F”と共に銀河系を旅しているヴァン(またヴァルコ)である。この儀式を遠くから見ながら、ヴァンはFに向けてこういう:「この星の民は自然を敬い、儀式を通じて共生してきた。」何故これを見せたいのかと聞くFに対して、ヴァンはこう付け加える。「この星は、古い友人のルーツだそうだ」。Fの反応からすると、その友人は恐らく自分のマスターであったと察することができる。そして、自然の良い面と悪い面の両方を認めて敬うこの惑星の民の価値観には、フォースに対してまた違う捉え方もあるではないかとヴァンが仄めかしていると思う。

Asu and Haru then cast their gaze to the view that stretches from that height all the way to the horizon. The first thing we see is supposedly their shared memory as children. Magina shows them playing with their friends at the river, lining up stones in an effort to change the direction of the current and guide the fish to where they want them to go. At that moment, we see the ground torn asunder by the power of Magina, with the mountains falling away and the course of the river being changed violently. Like those of us in the audience, the main protagonists of this tale have been following the betrothed as they make their way up the mountain: “F”, a former Jedi, and her galactic traveler companion Van (Valco). Taking in this ritual, Van says this to F: “The people of this world have a deep respect for nature. Their rituals allow them to live in harmony.” When F asks if that is why he wanted to show her this ritual, Van replies: “Only because an old friend of ours had roots on this planet.” We can surmise based on F’s reaction that this friend was her former master. I also feel that in showing the worldview of this planet’s people, one which acknowledges and reveres both the good and bad in nature, Van is seemingly hinting at another way to view and approach the Force.

Source: StarWars.com

このシーンをはじめて見たとき、日本の文化と宗教観の研究者であった(故)梅原猛氏のある言葉を思い出した: “仏教伝来を遥かに遡った古から日本列島で育まれた「神道」は自然の両面を崇拝すると同時に警戒していました。自然の恐ろしさに捧げ物することによって、恐ろしい自然を恵みの自然に変えていく。自然は一面怖い暴君の恐ろしさを持つと同時に、一面慈母のような優しい面を持ちます。” 梅原が言うように、このシーンではアスとハルを始め村の人たちがマギナ、つまりフォースのあらゆる面を敬って受け入れることを描写している:自然の恵みとなる川とそこに棲む魚、そして村の生活圏を破壊でも出来る地震や天然災害。

When I first saw this scene, the following passage from Takeshi Umehara, who was a scholar of Japanese culture and religious thought, came to mind: “Long before Buddhism came to Japan, the people of these islands both revered and feared the two faces of nature through Shinto. Within Shinto, people gave offerings in an effort to appease the fearsome side of nature and transform this power into a source of bounty and blessing. Shinto essentially acknowledges that nature is both an awful tyrant and charitable mother figure.” In echoing what Umehara says, this scene shows how Asu, Haru, and the people of their village revere and “accept” all the different aspects of Magina/the Force: the bounty of nature found in the river and the fish in its waters, as well as the earthquakes and natural disasters that can potentially destroy their village.

ここで塀和監督の言葉に戻りたい。この短編を通して表現としようとしたのは「フォースの中間点」である。この「中間点」を「中間領域」にも読み替えると拙者が思う。人間と自然の共存、要するに人間と自然の調和に必要なのはこういう中間領域である。そこにバランスが取れる。このバランスも「村の花嫁」にも意識されていた。塀和監督はこういう: “「スターウオーズ」の核にあるフォースとバランスという二つの概念を探る、「調和」の物語である。フォースの元になったとされる神道とスピリチュアルな世界へと回帰していくこの短編では、自分を見失い、フォースの光と闇のどちらに属することになるか確信を持てない謎のジェダイ、エフの葛藤も描かれている。”

Here I’d like to return to what director Haga said about how he wanted to portray a “middle ground” for the Force through this short. The Japanese word used in his quote was “中間点 (chuukanten)”, and I feel this can also be rephrased as “中間領域 (chuukan ryoiki)”, which shares a similar meaning. This middle ground is essential for human beings and nature to coexist and live in harmony together. “The Force and the notion of balance are two concepts that lie at the heart of Star Wars,” Haga says. “The Village Bride is a story that explores this idea of harmony between the two. It goes back to Japan’s native religion of Shinto and the spiritual realm that serve as the basis for the Force in Star Wars, with the main protagonist being the mysterious “F”. Having lost her sense of self and confidence, we see her grapple with the search to find which side of the Force she stands on: the Light, or the Dark.”

では、この中間領域においてどのような原理が働いているであろうか?この点について参考になるは心理学者であった河合隼雄(かわいはやお)が唱えた「中空構造日本」の持論である。河合氏によると「日本文化の中心は、空っぽなのだ」。この中空構造日本を初めて耳するきっかけとなったのは2015年の正月にNHKで放送された「日本人とは何もか?」というテーマを取り上げた「100分de名著」のシリーズの特集であった。ちなみに、4人の研究家・専門家(松岡正剛、赤坂真理、斎藤環、中沢新一)で編成されたこの座談会の内容が一冊の本にもまとめた。

The question then is what kind of principle is at work in this middle ground. I believe a good point of reference is the idea of “Japan’s empty framework” put forward by Hayao Kawai, a Japanese scholar of psychology. According to Kawai, the core of Japanese culture is in essence “empty space”. The first time I heard about this concept was in a special New Year’s day broadcast of NHK’s series “Famous Works in 100 Minutes” back in 2015, with this discussion centering on the idea of getting to the heart of what defines Japanese. The discussion held by the four scholar panel (Seigo Matsuoka, Mari Akasaka, Tamaki Saito, Shinichi Nakazawa) on this broadcast was later compiled into a book.

Source: NHK

日本の神話には、正体不明の謎の神様というのが、必ず出てくると共通点に河合氏が注目を当てた。「それぞれの三神は日本神話体系のなかで画期的な時点に出現しており、その中心に無為の神を持つという、一貫した構造をもっていることがわかる。これは筆者(河合)が “古事記”神話における中空性と呼び、日本の神話の構造の最も基本的事実であると考えるのである。」河合氏が取り上げる典型の例は古事記の冒頭に登場する三人の神:アメノミナカヌシ (天之御中主)、ツクヨミ (月読)、とホスセリ (火須勢理)。アメノミナカヌシとホスセリ (火須勢理)はちゃんと有為な神として扱われている一方、ツクヨミは何もしないです。河合氏がこの神話の構造をこう説明します:「日本神話の中心は空であり、無である。このことはそれ以後発展してきた日本人の思想、宗教、社会構造のプロトタイプとなっていると考えられる。」

One common feature present throughout Japanese mythology that Kawai zooms in on is the presence of an obscure divinity. “In Japanese myths, we consistently see three divinities appear at key moments within the narrative. The central figure of these trinities is always an idle divinity that does nothing. I (Kawai) refer to this as the “emptiness” of the Kojiki lore, and it represents the most fundamental truth within all Japanese legends.” Kawai calls attention to three divinities that appear at the beginning of The Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters): Amenominakanushi, Tsukuyomi, and Hoseseri. While Amenominakanushi and Hoseseri are depicted as active players in the narrative, Tsukuyomi does absolutely nothing. Kawai explains this mythological structure as follows: “The very core of Japanese myths is empty, indeed nothingness. This structure provided the prototype for the underlying make-up of all Japanese thought, religion, and society that have developed from that point (ancient times) forward.”

Source: NHK

この中空構造に関して、松岡正剛が注目するのは「中心は空(うつ)である」との点だ。以前この松岡氏が唱える「現(ウツツ)」が派生させる「移ろい」というコンセプトを考察する記事を書いたこともあるだけど、ここで松岡氏が同様のコンセプトは河合の唱える中空構造の仮説に置いて働いていると言う(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。“中心に「ウツなるもの」を置き、それがあることによって両脇の二つが動いているという河合の仮説には納得のいくものがあります。一見空っぽだが、いざとなるとそこに何かが湧き出てきたり、力が潜んでいたりする。信号に青と赤のほかに黄色があるように、A/非Aという二尺せず、真ん中に三つ目を置くことによって、どちらも生かすのです。日本人は中空構造に無意識であるかゆえなのか、方法的なことをかなり特別に意識し、大切にしていると思います。そうしないと中空に異質なものが入ってきたときに、大変な事態になりかねない。”

Matsuoka’s draws attention to the “empty core” concept and states how the “空 (kuu, void or sky)” character in the word “中空 (chuukuu)” can also be read as “utsu.” This reading is derived from that of the character “現 (utsutsu, the now)”, which in turn gives rise to the idea of “移ろい (utsuroi, change or transition)”. I have explored this idea in a previous post, so check it out if you would like to learn more. Matsuoka argues that this same concept is at work within Kawai’s “empty core” hypothesis (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese). “I believe there is some weight behind Kawai’s proposition of a three-part structure centered on something empty, but with that void putting the two sides into motion. At a glance it appears there is nothing but emptiness, but out of necessity this void can give rise to something, or transform into this well of latent power. A stoplight has not just red and green, but also yellow. It’s more than just A or not A; putting something in the middle allows us to keep both. Japanese people pay special attention to the processes behind things, perhaps because of this functional emptiness at work within their subconscious, and really cherish them. They have to clue in on these processes, for failure to do so can cause things to fall apart when something alien enters that void.”

中沢新一が河合の中空構造をこのように解釈する。“宇宙を作るには三項が必要だが、三項目は潜在的で表へ出ない。日本の神話において、天と地、海と山という二元論の起源はバーチャルで、このバーチャルに一項が与えられている、というのが河合さんの基本的な直観なのではないでしょうか。人間は、自然な状態だとこの思考方法が一番合理的で、例えば中空領域を置くことで、お互い妥協を図ることができます。自分と違うものを排除するのではなく、相手の原理を自分の中に入れることが可能になってくる。”

Shinichi Nakazawa has this take on Kawai’s concept of functional emptiness. “You need three elements to form the cosmos, but the third is this latent force that never comes to the forefront. In my view, Kawai’s basic hunch is that an extra element is added to the virtual base underlying the dualistic facets of Japanese legends, such as the pairings of earth and sky or sea and mountain. This is the most logical mode of thought for human beings in our most natural element. In allotting this empty space, we create an area where we can work things out and reach a compromise with one another. Rather than simply eliminating what is different from you, it becomes possible to take the tenets of the “other” and make them a part of your being.”

Source: NHK

中空構造という原理が動いている例として中沢氏が注目するのは日本の里山である。“その例として典型的なのが、日本の風景は、中間領域を残しておくことが基本になっています。人間と、山の生き物。二つが重なり合うところに里山を作る。里山は中間領域ですから、人間にとっても、昆虫や魚、動物にとっても素晴らしい住処(すみか)にも成り得る。生き物の要求する生存条件を認めているわけです。”

One example that Nakazawa cites as a place in which the functional emptiness concept is at work is the satoyama. “Japanese landscapes provide us with great examples of this principle at work, for they are based on the idea of leaving some form of middle ground. This is the satoyama (里sato for “village” and 山yama for “mountain”) concept, or the idea of a place where human beings and life on the mountain come together. A satoyama holds the potential to be a truly wonderful place for all life—human beings, insects, fish, and animals—precisely because it is a middle ground. It’s an acknowledgement of all the conditions for subsistence that living things seek.”

「村の花嫁」で描かれる村はまさに理想な中間領域を具現する里山。この里山において、自然(=生けるフォース)のあらゆる面と結べる領域が発生し、自然の力を有効的に活・生かしつつ共生の関係が醸し出される。また、この里山には松岡氏が語る「中空(うつ)・現 (うつつ)と移ろい」の原理が働いていると拙者が思う。里山はその意味で中空(うつ)だから、自然を排除することはなく、生けるフォースたる自然の移ろいと上手く調和できる器(うつわ)になる。「中空」を英語にすると「void」となり、英語に置いてこれは割りと「負」の意味合いが強い一方、日本語に置いてこの「中空」という概念は割りと「正」の意味合いも含まれることもある。これを念頭に理想のジェダイの象を描こうとすると、ジェダイは「中空」のフォースの器になることに辿り着くではないか。器として自分の中でフォースの調和を整えられていく。

The village depicted in The Village Bride represents the ideal middle ground that the satoyama embodies. Here we see the cultivation of different forms of coexistence, rooted in the connections with the various aspects of nature (i.e., the Living Force) that allow this power to be channeled. In addition, I also feel the concepts of “中空 (utsu, void)”, “現 (utsutsu, the now)”, and “移ろい (utsuroi, change or transition)” are at work in this satoyama framework. In a certain sense, the satoyama is an open void, and it does not expel the natural but rather serves as a vessel that deftly allows for the transitions within the natural to be in stasis, in harmony. As seen previously, the word “中空 (utsu)” tends to be translated as “void” in English, and this word carries some negative connotations within the English language. However, in Japanese it can assume a more positive notion of emptiness. Taking this latter idea as a basis for drawing up the ideal Jedi, we come to a Jedi that is an “empty vessel” for the Force. They serve as the void within which the Force can balance itself out.

Source: StarWars.com

惑星コルサントにあった旧共和国のジェダイ寺院は自然ではなく、もうはや自然の環境に代わって文明の利器で整えられた「人工的な環境」に置かれていた。しかし、古代のジェダイの寺院はそうではなかった。惑星ローサルとアクトにあったジェダイ寺院はその典型的な例である。両方の寺院は、文明から離れて完全に自然に囲まれた環境に位置され、自然と合体していた。そして、この二つの寺院には闇と光、いわゆるフォースの光明と暗黒が呼応し合える「中空」があった。アクトの寺院は海の水面から聳え立つ崖の島にあって、そこには深く暗い潮吹き穴があった。この潮吹き穴に暗黒面の力が宿っていて、それがレイを呼び掛けていた。レイがその呼びかけを拒むことではなく、何かを見せたいと察知し、一旦呼応することにした。最終的にこの呼びかけは暗黒面への誘いとならず、レイにとってフォースの全体の在り様をより理解できる教訓となった。アクトの潮吹き穴の体験のお蔭で、フォースを活かせるには自分自身にもっと振り幅を持つ必要があることをレイが知ることが出来た。つまり、フォースに寄り合って共生する道を歩む最初の一歩はアクトで踏み出した。

The Jedi Temple on Coruscant during the days of the Old Republic was completely removed from nature, and instead surrounded by an environment that was artificially constructed using the auspices of “civilization.” However, this was not the case with the ancient Jedi temples, prime examples of which include the temple on Lothal and the one on Ahch-To. Both of these temples were far removed from civilization, situated in a completely natural environment and essentially part of their natural surroundings. The two temples also possessed “empty spaces” for the Light and Dark Sides of the Force meld and interact. In the case of the temple on Ahch-To, which was situated on an island with cliffs standing tall above the ocean surface, there was a cavernous, deep space where the tide from the sea could well up. There was a Dark Side presence in this place, and it called out to Rey while she was on the island. Rey did not reject this call, but rather recognized that this side of the Force wanted to show her something. In the end, her response to this call from the Dark Side did not lead her down that dark path, but proved to be a lesson that helped deepen her understanding of the broader nature of the Force. The experience in the tide portal on Ahch-To enabled Rey to understand that she needed to have greater flexibility in order to better channel the Force within herself. It marked the first step on her own journey to co-exist and better sync with the Force.

Source: StarWars.com

一方、惑星コルサントにあったジェダイ寺院にはフォースと純粋に共存する余裕はなく、逆にジェダイ・オーダーが無意識にフォースを無理矢理にオーダーなりの「理想の形」に象らせようとした。つまり、フォースを活かせる「器」に必要な機能的な「中空」は惑星コルサントにあったジェダイ寺院にはなかった。それはその寺院の建立の話にも深く関わっているとも言えよう。寺院は古代シスの神殿の上に建立された歴史がある。要するに、ジェダイ・オーダーはフォースの「負」の面である「暗黒面」を遮断すると同時に、ジェダイ・オーダーの存在意義を守る目的のため寺院を建立した。「不安定」に対する恐怖に突き動かされ、敢えてその中空構造の機能を寺院とオーダーから無くしてしまった。

On the other hand, the temple on Coruscant did not provide much breathing room that allowed for the Jedi Order to truly co-exist and live in harmony with the Force. The opposite was true. Without realizing it, the Order tried to “force” the Force into what they believed it was its ideal form. In short, the Jedi temple on Coruscant lacked the functional void essential to channeling the Force. The argument can be made that the absence of this void was intricately tied to the very origins of the temple on Coruscant. History says that it was built on the ruins of an old Sith palace. In that sense, the Temple worked to both shut out the “negative” aspects of the Dark Side and protect the raison d’etre of the Jedi Order. Driven by fear of instability and flux, they ended up forfeiting the functional emptiness of the Temple and the Order at large.

ここで一旦「日本人とは何もか?」の斎藤氏の話に戻る。中空構造に潜む危険性に対して河合氏が警鐘を鳴らしたと斎藤氏が言う。その中心が空であることは、一面極めて不安であり、何かを中心に置きたくなるのも人間の心理傾向であると言えよう。河合氏が残した警告は次の通り:「今度中心への侵入を許した場合、日本の中空構造はもはや機能しないのではないか。」河合が警告した通り、ジェダイオーダーは「オーダーの存在の意義」に対する執着と「暗黒面に対する否定感」をその中心に置き、自ら中空構造を機能しない構造にしてしまったとも言えよう。

Here I’d like to go back to Saito’s thoughts in the Getting to the Core of Being Japanese discussion. Saito shows how Kawai warned of the danger inherent in this empty-core structure. The fact that there is nothing in the middle gives rise to a highly unstable quality. When faced with such instability, Kawai claims that human nature makes us want to put something in this middle ground. Kawai left us with the following warning: “The next time we let something encroach upon this middle space, Japan’s empty-core may very well cease to function.” True to Kawai’s words, the Jedi Order filled this middle space with their fixation on their raison d’etre and rejection of the Dark Side. In doing so, they became the architects of a structure/order devoid of functional emptiness.

フォースの光と闇のどちらに属することになるか確信を持てなかったFは、マギナと「共生」する村人の生活と価値観に自分なりの中空構造を見出したではないかと拙者が思う。自分自身がどちらに属するではなく、フォースを活かせる器となり切って新な共存・共生を模索することにしたとも言えよう。そう決意したのは、次のセリフに窺える: 「川に石を投げても、川の流れは変わらない。でも、自然と調和して共に変わっていく。その心、あなた達は知っているはず。命の息吹は風となって、必ず応えてくれる。マギナよ、立ち昇りたまえ。そして、フォースと共におらんことを。」

As stated earlier, our protagonist F in The Village Bride is uncertain of which side of the Force with which she will cast her lot. Yet, in seeing how the people of the village live in harmony with Magina, and in observing their lifestyle and values, I believe that F discovered her own form of functional emptiness. In the end, she does not pick a definitive side, but seems determined to discover a new way of co-existing and living with the Force, one that involves refashioning herself as a vessel for channeling it. This resolve can be seen in her own words: “You can’t change the river’s flow by casting a stone. But live in harmony with nature and you’ll change together. The people of this world know that well. You know that the breath of life becomes wind and will always respond. Magina, may you rise, and, may the Force be with you.”

Source: StarWars.com

このセリフの日本語の吹替を聞いたとき、注目を引き寄せた言葉は二つあった:「調和」とスターウオーズの名言を代表するMay the Force be with Youの邦訳に用いる「共に」。ここで自然をテーマとする話に用いると、この「共に」を「共生」と言い換えるもできるし、それはまた「調和」と言い換え解釈するではないかと思う。つまり、フォースの全ての面と共生する。吹替の邦訳を作る段階でこの繋がりは敢えて意識されたかわからないけど、その連想を見事に成り立たせると思う。なかなか上等な翻訳だ。まさFが辿り着いた「フォースと共に生きる」という教理がこの名セリフに潜めていた。これはまた、いい邦訳がスターウオーズの世界観を拡張する素晴らしい例である。

When I first heard the Japanese dub of F’s little soliloquy, I instantly zeroed in on the words “調和 (chowa: “harmony”)” and “共に (tomo ni: literally means “together with”), with the latter famous in the Japanese translation of the iconic Star Wars line “May the Force be with you (Force to tomo ni oran koto o).” Bringing these words to the subject of nature, we can switch out the Japanese word “tomo ni” with “共生 (kyosei: “live together”)”, and in turn I feel that “kyosei” is synomous with “chowa.” Essentially, what we have is living together with all aspects of the Force. I’m not sure if this line of thought was being followed in the translation, but it certainly lines up beautifully. What a great Japanese translation. On top of that, it inherently conveys that truth of “living together with the Force” that F arrived at. All told, this shows how a superb Japanese translation can bring even greater breadth to how we take in the Star Wars universe.

The Bridge Between Light and Dark: Princess Mononoke, Duality, and the Force 闇と光の掛橋:もののけ姫と双対性、そしてそこに窺えるフォース

スターウォーズの世界観を形成する概念と言えばまず「フォース」が思い浮かぶのだ。このフォースには「光」と「闇」とそれぞれの面で構成され、オリジナルトリロジーでは主人公であるルークスカイウォーカーを通して「光」がどのように「闇」に克服されるかが描かれている。フォースは「光」と「闇」の二重性を持ちつつ、ジェダイが基本的に「闇」を否定し、フォースの「光」に頼る道を選ぶ。その闇に対する否定感を醸成させた「恐れ」はこのヨーダの名言に窺える:

The Force is sure to come to mind when thinking of concepts that help shape the worldviews of the Star Wars saga. It consists of two sides, the light and the dark, and in the original trilogy Luke Skywalker is used as the vehicle for showing how the light vanquishes the dark. Despite the inherent duality of the Force, the Jedi essentially reject the dark, eschewing a path grounded in the light. The sense of fear fomenting this rejection of the darkness is encapsulated in this classic line of Master Yoda:

「一度、闇の道を進み始めたら、闇が一生を征服し、食い尽くすじゃろう。」

“Once you start down the Dark Path, forever will it dominate your destiny, consume you it will.”

要するに、フォースの一面である闇を恐れるのあまり、ジェダイがその面をフォースから切り離そうとする教義を成立させた。その結果、フォースの二重性を見失って、不安定の方へ傾いてしまった。ただし、皮肉にもヨーダによると、「恐れ」こそが闇へ導いてしまう。

In short, the Jedi’s consuming fear of the Dark Side gave rise to a dogma that essentially sought to sever the darkness from the Force. This caused them to lose sight of the inherent duality of the Force, tilting them towards the plane of imbalance. Ironically, Yoda himself said that it was fear which lead to the Dark Side:

Source: Wookiepedia

「恐れはダーク・サイドに通じる道じゃ。恐れは怒りを呼ぶ。怒りは憎しみを呼ぶ。憎しみは苦しみを呼ぶ。」

“Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.”

一方、日本へ目を向けると、二重性のある価値観が昔から大切にしてきた。独特の編集工学を確立している松岡正剛がこれを「デュアルスタンダード」と呼んでいる。松岡著作の「日本文化の核心」ではこの「ヂュアルスタンダード」をこう解説する: “デュアル”とは「行ったり来たり出来る」ということ、また「双対性(デュアリティ)」を活かすということです… こうして、(日本において)和漢の相違の共存と変換を仕組んだことが漢風文化と国風文化という対比を形作っていくことになるのです。”

Meanwhile, Japan has long cherished a view grounded in a sense of duality. Seigo Matsuoka, a Japanese scholar who has fashioned his own original style of “editorial engineering”, refers to this as Japan’s “dual standard”. He provides a nice explanation of this in his book The Core of Japanese Culture: “This idea of ‘dual’ in Japan implies this sense of going and coming, of being able to apply this sense of duality. With this approach, Japan was able to produce a fertile soil in which Japanese and Chinese culture could co-exist and be refashioned; this gave rise to this duality composed of Chinese and indigenous Japanese culture.”

この「双対性(デュアリティ)」は「もののけ姫」を初め多くの宮崎駿監督の作品に現れている。「もののけ姫」の宣伝コピーを担当した糸井重里は1997年に映画の公開前のンタビューでこう語った: “「ナウシカ」の辺りからそうなんですけど、宮崎さんの中では、物事を善悪で切ってないんです。勧善懲悪で物語に決着をつけない。これは宮崎作品の根底にあるものの一つであって、だからこれだけ人の心を惹きつけているものである。善悪を超えたものという思想が、前は通奏低音みたいに流れていたのが、今回はメロディをとっている。そうかと思うと、自然と人間というもの、宮崎にとっては対立項ではない。自然だ、人間だ、善だ、悪だっていうものが全部 “ただある”状態で世の中にあるわけですよね。」

The idea of duality is something evident in many works by Hayao Miyazaki, including Princess Mononoke. Shigesato Itoi, who was tasked with coming up with the catch copy to promote Princess Mononoke, elaborated on this in a special interview conducted ahead of the film’s release in 1997: “Nausica (of the Wind Valley) is one example that comes to mind, but Miyazaki’s way of thinking does not divorce good from evil. He does not finish his films on a note of poetic justice being served. This is basically a fundamental feature of the art he produces, and I feel that is what makes his films captivating for audiences. This idea that transcends good and evil previously served as the so-called basso continuo of his films, but in Princess Mononoke it is the melody. When you frame things this way, you see that Miyazaki does not view human beings and nature as being set against each other. Nature, humanity, good, evil… They all simply ‘just are’ in this world. That’s it.”

宮崎監督は漫画版『風の谷のナウシカ』のクライマックスで、ナウシカに以下の台詞を語らせている。「いのちは闇の中にまたたく光だ」と。これは、文明の全てを是として、「正義の光」にたとえがちな人間中心主義に対する宮崎監督流のアンチテーゼである。宮崎監督は、以前以下のように語っていた。

Hayao Miyazaki depicts Nausica making the following statement in the climax of the manga version of his tale Nausica of the Valley of the Wind: “Life is but a light flickering in the darkness.” This line embodies Miyazaki’s own antithesis to humanocentrism, which tends to view human civilization as the embodiment of justice, in the right and in the light. The following quotes here provides more insight into Miyazaki’s thoughts on this:

「アメリカ映画に限らないのですが、ヨーロッパからはいってくるファンタジーがありますが、光と闇が闘っていつも光が善なのです。悪い闇がのさばってくるのを、光の側の人間がそれを退治する。それと同じ考えが日本をむしばんでいると思います。」

“Western culture, and this includes both American films and fantasy works from Europe, always depicts light as the force of good in the battle between the light and dark. These works show human beings standing on the side of light, vanquishing the forces of darkness that seek to throw their weight around. I feel this line of thought is eating away at Japan.”

Source: The Princess Mononoke

「森と闇が強い時代には、光は光明そのものだったのでしょうね。でも、人間のほうが強くなって光ばかりになると、闇もたいせつなんだと気がつくわけです。私は闇のほうにちょっと味方をしたくなっているのですが。」(鼎談集『時代の風音』)

“Light was that ray of hope in a time when the forest and darkness held sway. However, as human beings grew in strength, light came to dominate everything. It was here that people came to recognize the importance that the darkness holds. In my case, I find myself more of a fan of the darkness.” (Three-person dialogue “Wind Song of the Age”)

Source: The Princess Mononoke

作中ではこの「闇たる自然」を敵対視するのはエボシ御前が率いるタタラ集団である。その集団の名前の通り、製鉄を行う拠点はタタラ場といい、そこは物語の主な舞台となるシシ神の森と隣接する。製鉄するためには樹木を焼いてたくさんの木炭が必要としていた。つまり、森を破壊せずに製鉄ができない。宮崎氏がこう語る:「農具に道具類。鉄は人間の生活を革命的に変えた。鉄を作るため、人は樹を切った。人類の歴史の繁栄は、樹を切ってきた歴史でもある」。森を伐採するのは、未開の世界(闇)を開拓された地(光)とすることだ。

Lady Eboshi and the tataraba (iron works) community she leads view the seemingly dark presence of nature as a threat. Their forge sits on the edge of the Shishigami forest, and serves as one of the main stages for the events of the film. The tataraba style of producing steel depicted in the film required lots of charcoal, and to do this they cut down lots of trees to create the charcoal to fire the forge. In short, the only way they could manufacture steel was by laying waste to the forest. Miyazaki describes it in this light: “Iron/steel transformed the fabric of human life, beginning with farm equipment and other tools. However, human beings needed to cut down trees to create this iron/steel. Viewed this way, the prosperity of human society is a history of destruction… the felling of trees.” In cutting down the trees that make up the forest (the darkness), human beings created and developed spheres of civilization (light) .”

この考えはエボシ午前がアシタカに向けて突き放す言葉に表れている:「森に光が入り、山犬共が鎮まれば、ここには豊かな国になる」。自然破壊者に違いないが、彼女は開拓と新しい産業の開発、その結果の経済力によって前人未踏の新しい共同体を作った。それも、虐げられ、さげすまれてきた人々を市民として。(The Princess Mononokeからの引用)

This facet of human history is reflected in the words Lady Eboshi flings at Ashitaka in describing the work of the tataraba: “We can make this a prosperous land. To do that, we need to put light into the forest and bring the wolf gods to heel”. The very work of the tatatarba entails the destruction of nature. However, Lady Eboshi perceives her mission to be the development of the land and the creation of a new industry that yields economic power. Her pursuit of this brought about a new form of communal existence, one that treated people who had been cursed and discriminated against as full-fledged citizens. (Source: The Princess Mononoke)

Source: The Princess Mononoke

ここで松岡氏の「ヂュアルスタンダード」の解説にもう一度戻りたいと思う。「“デュアル”とは「行ったり来たり出来る」ということ」。「もののけ姫」の全編を通してこれはまさにアシタカが実現している。タタラ集団(文明たる光)とシシガミの森(自然たる神秘の闇)の間に行ったり来たりしている。どちらにも思いを寄せながら、どちらも敵対視としない。自分が食らった呪いを解ける鍵となるのは、共存への道を切り開けることである。

Here I’d like to return to the notion of “dual standard” put forward by Matsuoka: “this sense of going and coming”. This is essentially what Ashitaka does throughout the entirety of the film of Princess Mononoke. He repeatedly goes back and forth between the tataraba, representative of the light of civilization and human society, and the Shishigami Forest, the sacred darkness of nature. He bears both in mind, but does not view either as an opposing force. The key to lifting the curse that has befallen him is blazing a path towards coexistence.

『もののけ姫』の物語の後、タタラ場に残ったアシタカは、サンと話し合いながら樹を伐り続け、動植物を殺して食べ、鉄を作り続けることになる。それは、余りに困難な共生構造である。だが、破壊と殺戮の中にしか人間の存続はない。その人間としての業を実感しながら生きることは、心に闇を持つことではないか。心を光で満たすことが人間中心主義の破壊と生命倫理の崩壊につながるのなら、逆に心に闇を持つことが破壊の抑制と生命倫理の再生につながるのではないか。(「もののけ姫読み解く:思想の物語」からの引用)

The ending scenes of the film show that while Ashitaka will stay in touch with San, he elects to remain at the tataraba (iron works). This means that he will work with the rest of the community as they continue to make steel, cutting down the trees of the forest and taking their sustenance (animals, vegetables, etc.) from nature. Through these scenes, Miyazaki hints at the incredible difficulty Ashitaka faces in his pursuit of coexistence. At the same time, though, we see how death and destruction are the sole avenues for the perpetuation of human existence. It seems that Miyazaki’s message here is that holding darkness in our hearts means owning up to our sins against nature as we live our lives. If we focus on filling our soul solely with light, we risk the destruction born of humanocentrism and the collapse of bioethics. Miyazaki appears to be making a case for harboring a bit of darkness in our hearts, arguing that it can help us curb the destruction we cause as human beings and restore that bioethical balance. ("An Intellectual Tale" from Dissecting Princess Mononoke).

Source: The Princess Mononoke

共に生きる道を選んだアシタカがやろうとしていたのは自然と人間社会の掛橋になろうとすることだった。それはまさに理想のジェダイの姿ではないかと拙僧が思う。闇と光の掛橋となって、行ったり来たりすることが出来る。これは松岡氏がいう「双対性(デュアリティ)」を活かす」こと。スターウォーズではアナキン・スカイウォーカーのパダワンであったアソーカ・タノのキャラクターデザインをしたときデイヴ・フィロニー監督がもののけ姫、つまりサンを参考にした話はよく知られている。しかし、内面的で見てみると、アソーカはサンよりアシタカの方に似ているではないかと思う。彼女がジェダイ騎士団を後にして、そしてジェダイの教義を捨てて、本来のフォースの掛橋の意味を探ろうとする道を選んだ。それはアシタカが追究する共存に候。

Ashitaka’s pursuit of co-existence can be taken as a quest to become a bridge between nature and human society. I feel this provides the ideal model of what a Jedi should strive to be: a bridge for passing back and forth from the Light and Dark. This equates to the application of duality that Matsuoka refers to. It is well-known that director Dave Filoni used San as inspiration for the character design of Ahsoka Tano, the Padawan of Anakin Skywalker. However, the inner qualities of the character of Ahsoka more closely resemble those of Ashitaka, in my view. In leaving the Jedi Order behind, she parted ways with their dogma and sought to discover what it meant to be a bridge of the Force. Essentially, that is akin to the very quest of co-existence that Ashitaka seeks to achieve.

Source: Ign Japan

出所:

「もののけ姫読み解く」

「The Princess Mononoke」

「日本文化の核心」

Sources:

Dissecting Princess Mononoke

The Princess Mononoke

The Core of Japanese Culture

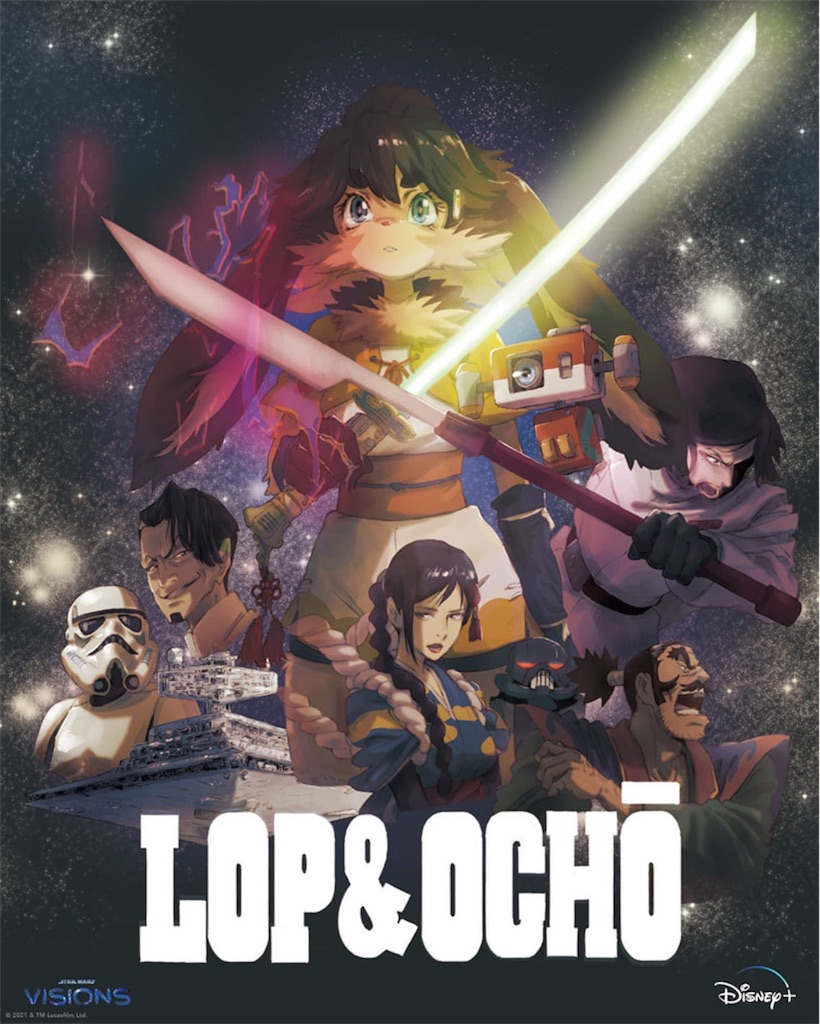

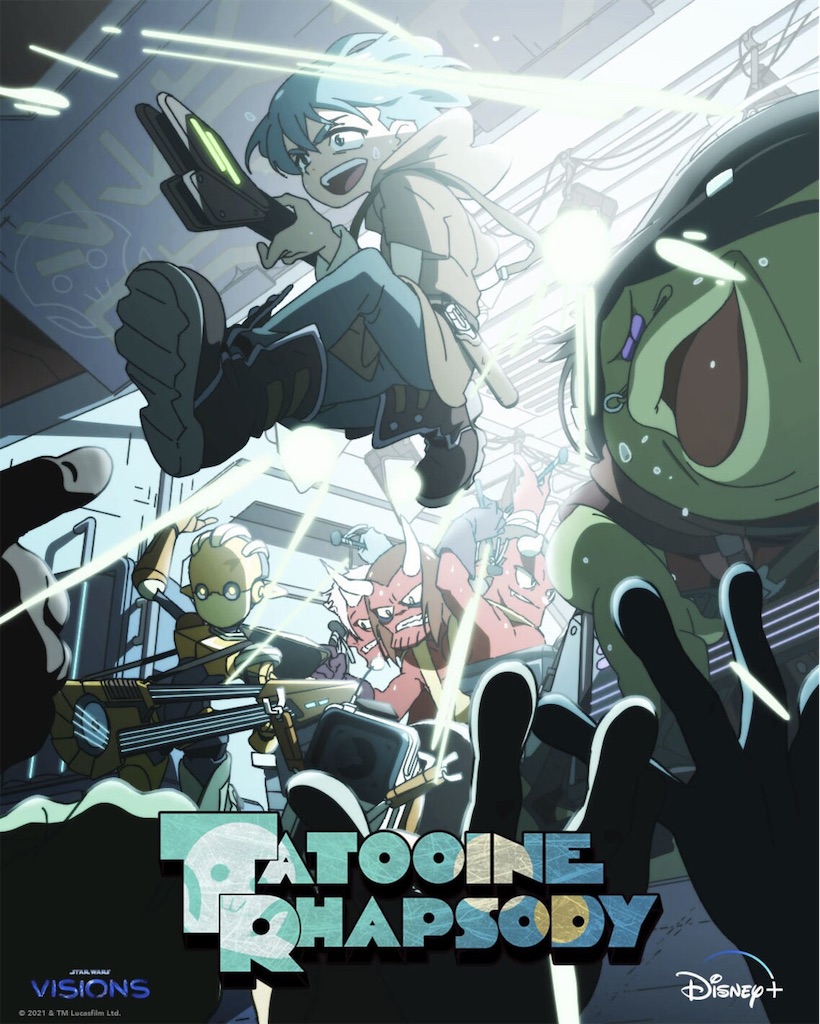

Conversation with "Star Wars: Visions" Directors of "Tatooine Rhapsody" and "Lop & Ochō"

日本語という言語の世界への入り口の一つはアニメだった。カウボーイビバップやるろうに剣心を初め、字幕版を見ながら新たに覚えた日本語を必死に聞き取れようとした。その語学的な目標を目指すと同時に、アニメの世界観と豊な表現力も当然堪能した。アニメのお蔭で拙僧の語学の旅に大きな一歩を踏み出せただけではなく、審美と美学に対する価値観がより豊かにもなった。

One of the avenues I used to venture into the world of the Japanese language was anime. I started with the likes of Cowboy Bebop and Rurouni Kenshin, watching the subtitled versions and trying really hard to pick out the new Japanese words I had learned. In addition to this academically driven goal, naturally I also enjoyed the vast expressive potential unique to anime. The medium not only helped me take my first major steps forward on my journey through the Japanese language, but also broadened my own artistic and aesthetic sentiments.

「スターウォーズのアニメ企画があるらしい」という噂を初めて聞いたときに感じたわくわく感は今も鮮明に覚えている。フォースに織り込まれている日本の宗教観を初め日本の文化がジョージ・ルカース氏が生み出したあの遥か彼方の銀河系に与えた影響が非常に大きかった。それを考えるとアニメを通してスターウォーズをその源(ソース)に戻すのは正しいと思った。「スターウォーズ:ビジョンズ」に関わった日本のアニメスタジオのクリエーター陣はスターウォーズから影響を受けながら、自分が想像するスターウォーズを日本の独特な媒体で新たな表現(ビジョン)を見せてくれた。その意味で、「スターウォーズ:ビジョンズ」で日本文化とスターウォーズの縁の輪が完成された。

I vividly remember the excitement I felt when I first caught wind of the rumors about a Star Wars anime project. The galaxy far, far, away conceived by George Lucas was heavily influenced by Japanese culture, such as the Japanese religious worldviews evident in the concept of the Force. In that respect, it felt right to see anime used as a vehicle for bringing Star Wars back to its source. The Japanese creators involved with Star Wars: Visions were all influenced by the saga, and using the unique Japanese medium of anime they showed us a new “vision” of Star Wars rooted in their own imaginations. In that respect, Star Wars: Visions completed that ring connecting the saga and Japanese culture.

Source: disneyplus.jp

下記の対談では、「スターウォーズ:ビジョンズ」の「タトゥイーン・ラプソディ」と「のらうさロップと緋桜お蝶」の監督の二人が自分の作品を始め、スターウォーズに対する思いを楽しく語り合う様子を窺える。元の対談記事はこのサイトから閲覧できるけど、その日本語をベースに英訳を作ってみた。今回の「スターウォーズ:ビジョンズ」は一度限りの企画で済まず、継続的に作っていく価値はあると拙僧が思う。

The following conversation brings together the directors of Tatooine Rhapsody and Lop & Ochō. They have a lot of fun discussing their own contributions to Star Wars: Visions as well as their own thoughts on the Star Wars saga. The original Japanese article can be found at this site, with my English translation below based on that article. I really hope that Star Wars: Vision is more than a one-off project. There is true value in continuing to make these shorts.

--(Interviewer) How about you guys start us off by introducing yourselves.

Igarashi: I’m Yuki Igarashi, the director behind Lop & Ochō.

Kimura: And I’m Taku Kimura, the director of Tatooine Rhapsody.

*Translation note: The word “Ochō” in Japanese means “butterfly”, and in the Japanese title it is preceded by the word “Hizakura”, which in English translates to “winter cherry blossom”. When you watch the short, you see visual elements sprinkled throughout that allude to the imagery painted by the title. The “hi” part in “hizakura” is written in Kanji as 緋, which means “scarlet” or “crimson”.

--So what did you think of each other’s work in Star Wars: Visions?

Igarashi: Tatooine Rhapsody was an absolute blast. It had that brimming sense of optimism you get when you watch Episode 4. At the same time, I felt it really pushed the envelope, for it’s the only real short out of the bunch that doesn’t throw in any of those chanbara (“sword frenzy”) elements. The slightly deformed aesthetic of the characters put through that kawaii (cute) Japanese filter was both fresh and equally ambitious.

Source: Wookiepedia

Kimura: Wow, that’s some high praise! I’m thrilled to hear that’s what you felt.

--Taku, what did you think of Lop & Ochō?

Kimura: I thought it was stunning. Simply wonderful. The visual aesthetic in the shots and art was top notch, right on par with what you’d see in a full-length film. That really impressed me. I also loved how you took that idea of “blood ties” that is so central to Star Wars but then explored how you don’t need to be blood relations to be family. I feel that message holds a lot of weight.

Igarashi: We really tried to create that feel of anime made in the 1980s and 1990s. The creators making anime at that time were influenced by Star Wars, so we looked at different ways of recreating that feel.

Kimura: Did you have a lot of younger people on your team?

Igarashi: Yeah, we had quite a few people that were on the younger end of the spectrum. There were also members on our team a decade or so older than me, such as artist Masaji Kaneko and mecha designer Shigeki Izumo. They’re of the generation that grew up on Star Wars, and dreamed about one day doing work which involved that galaxy far, far, away. However, it seems most of the creators working on Tatooine Rhapsody were on the younger side.

Kimura: Most of the team was pretty young. In fact, there were more than a few who knew little about Star Wars. That made it a bit tough for me, as I had to give them a crash course on the Star Wars world before we got to work. The galaxy has its own feel, so even the characters lurking in the background need to fit that vibe. This limits the scope of design in those characters as well.

Igarashi: One of the goals of these Star Wars: Visions shorts is to bring new fans to that galaxy far, far, away. I feel like many of the younger people in Japan today, in particular the female audience, have not really seen Star Wars. It’d be great if the work our young teams of SW newbies put in on Lop & Ochō and Tatooine Rhapsody get them to think, “hey, this galaxy looks like fun” (chuckles).

The Visions shorts made by the other directors had that veteran feel behind them. I think people that saw Episodes 4-6 when they came out probably have a bit of a different take and perspective on the saga. I almost feel like we owe them an apology of sorts, because we didn’t see the original saga in real time.

Kimura: Haha, that would’ve been amazing to see the films when they first came out. What was the first SW film you saw in the theater?

Igarashi: My family really wasn’t the theater-going type, so the first one that I saw at the box office was actually Episode 7. Before that, I watched all the original films and prequels when they were broadcast on TV. My face was glued to the television whenever I watched Star Wars. How about you? What was your first Star Wars theater experience?

Kimura: My first was Episode 3, but if my memory’s right it was only just barely. I was just a kid at that time, so I couldn’t set off to the theater when I felt like it.

Igarashi: I hear you. My theater experiences came after I was able to make my own money. I went to see The Force Awakens on opening day at the Toho cinema in Shinjuku. By that time I was also working in this industry as well.

Kimura: You mean the 6:30 p.m. showing!? *Translation note: First showings of TFA in Japan were on Friday opening weekend at 6:30 pm

Source: cinematoday.jp

Igarashi: No (laughs), I went to the showing right after that. But I did get to take in all the people dressed up like Jedi with their lightsabers for that first showing when I got to the theater. The start of the sequel trilogy (Episodes 7-9) was really special, for you could feel that energy and love for Star Wars. Those days were great.

Kimura: That’s awesome. I’d love to see something that brought back that festive atmosphere again. I saw The Last Jedi in Tokyo, but for The Force Awakens I went to a local theater in Shiga. There was nobody with lightsabers at that theater, which left me thinking “man, there are no Jedi in Shiga (laughs).”

*Translation note: Shiga is a prefecture in central Japan which is next to Kyoto. It is a fairly rural prefecture famous for the beautiful Lake Biwa

Source: The Nippon Foundation

--What did you think when you were approached about the Star Wars: Visions project?

Igarashi: Honestly, I thought “is this a scam or something” when I first learned about it. About three days after the parts of the anime Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken I did were aired on TV a person at Twin Engine sent me a mail asking if I’d like to get involved in contest to make a Star Wars anime. Seeing a Gmail address made me think something was up (laughs). I’ve heard a similar thing happened to Dave Filoni, the director of The Clone Wars series. He thought someone was joking with him when he first received the call about that project.

Kimura: I’ve heard that story, too (chuckles).

Igarashi: The scope of the pitch they made for Visions intrigued me. I mean, they basically told us to make a new style of Star Wars, encouraging us to bring our own originality to it and feel free to go beyond the bounds of what already exists. In trying to figure out how far to go with refashioning that galaxy far, far, away, I started thinking about that core essence of Star Wars. I was thoroughly engrossed in The Mandalorian around that time, and that gave me a nice angle in how to approach Visions. Just like that show does, I aimed to create something that the general audience would love, but throw in some Easter eggs that the hard core fans would enjoy. In doing that, I strove to make something that new fans would appreciate.

Source: starwars.com

Kimura: When I first learned about Visions, I didn’t really consider myself as the person that would be involved. I thought that someone else would end up doing it. However, when we got the green light for our story, I began wondering if I was really up to the task (chuckles). Even when work on our short got underway, it never really sank in that I was doing Star Wars. As you said, they pretty much gave us carte blanche to do what we want. I expected most of the other shorts to go with something that put Japanese culture front and center, paying homage to that Kurosawa influence, or throw in a lightsaber. With this in mind, I tried to go a completely different route, and this led me to do something with music.

Igarashi: Did you have any personal reason for trying to do something with music, specifically rock?

Kimura: Rock has this rebellious streak to it, so I looked to tap into that and portray a band of four that were standing up to the establishment. One thing in Star Wars I really like is how Episode 4 and the Rebels series focus on that team collective. I also felt that if they have jazz music in Star Wars, there is bound to be other styles of music in that galaxy far, far away as well. My decision to go with rock reflected that desire to broaden the musical horizons of Star Wars.

Igarashi: So you didn’t go with that idea because you do music yourself?

Kimura: Haha, sorry to disappoint, but I’m not a musician. I do love listening to it though.

Igarashi: The stillness of the crowd in that first scene of the band playing live really reminded of clubs in Koenji, so I thought you might have firsthand experience with something like that (chuckles).

*Translation note: Koenji here refers to the area around the station of the same name. It’s on the Chuo Line, a train line that runs east-west through Tokyo, and only a couple of stops from Shinjuku. It has a lot of unique bars and music clubs.

Source: Urban Life Metro

Kimura: Actually that scene was based on my own experience of going to see my college friend’s band in concert.

Igarashi: One thing that struck me about the concert scenes was that droid spinning round and round and not actually playing anything.

Kimura: That droid was modeled off of a speaker. You guys had a droid in Lop & Ochō as well. I feel that droids are staple of Star Wars, given how they show up in most of the other Visions shorts.

Igarashi: Throwing in some droids does give it that Star Wars feel. There is a soft and fuzzy evenness to them.

Kimura: Droids really help to lighten the mood in those heavier scenes. I think we made the right decision in adding some droids. Hopefully they can make some merch out of them. I’d buy it.

Igarashi: That was one of my goals with our Visions short (laughs). I’ve always felt that there’s no separating the toys from Star Wars, and vice versa. I’m still waiting for them to make some Visions merch or toys (laughs). The whole Visions project has this omnibus feel to it, and with each studio trying to portray what they think is the best aspect of Star Wars, I think that together we have created something that is readily accessible to new fans. Actually, I was quite surprised to see how much variety there was in the Visions shorts. I found myself applauding the work of others and thinking to myself, “that’s something I wanted to do (chuckles).”

Kimura: I don’t have any regrets with my work on Visions because that was what I choose to do. In saying that though, the once-in-life time nature of this project does have me wishing a bit that I had thrown in some lightsaber action (laughs).

Igarashi: Yeah, I also wanted to take our story to outer space. In starting Lop & Ochō out in space, it would have kind of overlapped with some of the other shorts.

Kimura: Putting in a famous line like “I’ve got a bad feeling about this” did that too.

Igarashi: Overlapping in a bunch of different areas ended up working out, I feel, for it helped convey and boil down the essential elements of Star Wars for new fans.

--Speaking of overlap, Yoshihiko Dewa did the music for each of your shorts. What did you have in mind when approaching him to handle the score?

Igarashi: I’ll let you go first, Taku, since there are a lot of music elements in the Visions short you did.

Kimura: Sure thing (laughs). I admit that I didn’t feel right about taking an existing SW track and doing something rock with it. I mean, the music is a big part of what makes Star Wars, Star Wars. Given the challenging nature of what we were asked to do with Visions, I opted to go for it with a gutsy rock track. Still, I wasn’t completely comfortable with that. The frustrating part was that we had to tell Mr. Dewa what we wanted before the animation was complete, which meant that all the instructions and input from our side ended up being a little abstract.

Source: Starwars.com

--The general consensus on social media is that voice actor Hiroyuki Yoshino knocked it out of the park with his music vocals.

Kimura: Actually, I have a little confession and apology I need to make. We recorded the vocals for the song first, and it was sung by somebody else. It wasn’t until later that we went with Mr. Yoshino, but you really can’t tell the difference because the performances sound so much alike. Hopefully fans can appreciate this bit of trivia (laughs).

Igarashi: Whoa, I would have never noticed! So what kind of song and vocals did you ask Mr. Dewa to make for you?

Kimura: The band I had in mind was Kuro Neko Chelsea (Black Cat Chelsea). I like that husky quality of the lead singer’s voice, so that’s the style of song I asked Mr. Dewa to make. Basically something that didn’t sound too pretty. The music in Tatooine Rhapsody stuck with that rock vibe throughout the entire short, but when I heard the music for Lop & Ochō, I was blown away by the incredible breadth of the music that Mr. Dewa created for you. It really felt like Star Wars.

Igarashi: With Lop & Ochō, I wanted to vary the tracks between Western orchestral music and pieces performed on traditional Japanese instruments. That’s what led me to turn to Mr. Dewa, as I felt he was really the only person who was up to the challenge of tackling such a wide variety of musical genres. That gut feeling proved to be on the mark when I heard the demo he made for us, for the music had that Star Wars feel.

We tried to go with a film score-style for the overall tone of the music. This is different from the general approach to music for anime, and posed its own unique challenges, such as trying to match the pacing of the music with what was unfolding on screen. That said, tackling this bit was also fun. We went with an orchestral style piece for the opening scene with the Imperial Star Destroyer descending on the planet. For our main protagonists, we used Japanese style pieces featuring Japanese and other Eastern musical instruments. Towards the end, we decided to blend these two styles. Recently I’ve been playing Ghost of Tsushima, and the score for that game features a blend of Japanese instruments and Western orchestra. That was a point of reference I gave to Mr. Dewa in making the music for Lop & Ochō (laughs).

Source: In game shot of Ghost of Tsushima by author

--Was there anything you found to be difficult in creating these Visions shorts?

Kimura: The toughest thing for me was that this was my directorial debut. But I tried to put up a steady front, as I felt it would be me as the director to look indecisive or weak in front of the team I was leading. The members of our team were really fantastic, so other than this being my first time in the director’s chair, I really didn’t have much difficulty. Everything in production went smoothly. Disney and Lucasfilm also were pretty receptive, and vetoed very little of what we proposed. I was worried they wouldn’t let us put in the big names like Jabba the Hutt and Boba Fett, but they loved those ideas and gave us the green light (chuckles).

Source: starwars.com

Igarashi: We had our basic concept in place early on, but the question then was how far we’d go with bringing out those Star Wars elements. We changed our mind a couple of times there. Our initial plan was to going with something pretty ambitious, but in doing that we feared it would lose that Star Wars feel (laughs). That led us to change course, and eventually settle on that hybrid approach. Our aim was to create something that new fans would enjoy, while also delivering something that would stand up to the demands of hard core Star Wars fans.

Speaking of hard core, Shigeki Izumo, who did all the vehicle and mecha designs for Lop & Ochō, is a massive Star Wars fan who really knows his stuff. I mean, this guy ran a Star Wars site for fans in Japan. He recommended that I read Joseph Campbell’s book, and so I did (laughs). The notes that he showed me were pretty interesting, and included things like the stuff that was conveyed to the studios in the States. Another passionate Star Wars fan on our team was Kaneko, who handled the art for our short. Having these hard core fans on board and ready access to their knowledge was a huge help as we fleshed out the details for Lop & Ochō.

Kimura: I wasn’t as lucky, for most of the people around me didn’t know all that much about Star Wars. That meant I ended up having to do the lion’s share of the research (laughs). I mean, I love Star Wars, but I don’t know everything about that galaxy far, far, away (chuckles).

Igarashi: Today there are literally loads of books you can get your hands on, making it overwhelming to read up on all the details of that galaxy. Searching out the old book stores is also a tough task. It’s pretty hard to get up to speed on Star Wars if you were unable to witness all of it in real time.

Kimura: They keep coming out with all kinds of new merch, too (laughs).

Igarashi: You pretty much have to narrow your focus to a few areas, otherwise you’ll fall into a bottomless pit. I’ve got into the little carded figures for The Mandalorian.

Kimura: I’m a big fan of The Mandalorian, too.

Igarashi: It’s such a great series. Season 2 had a kind of MCU feel to it with all the different characters (from other parts of the saga) assembling. I actually worried they’d steal the show (laughs). Indeed, the characters we meet in The Mandalorian are all so good. That series was always in the back of my mind as we worked on Lop & Ochō.

Kimura: Seems like the family sword (that Lop receives) was inspired by the Dark Saber (laughs).

Source: Sci-fi and Fantasy Network

Igarashi: The Mandalorian is simply awesome. I’d love for them to do a full-length film. All this talk of what we love about Star Wars could keep us hear for ages. We should geek out on Star Wars over some drinks some time (laughs).

--In winding this talk down, is there anything particular thing you’d like to ask your fellow director here?

Kimura: The fruit in the market scene in Lop & Ochō really reminded me of the Meiloorun melons in Rebels. Was that the same fruit (laughs)?

Igarashi: That fruit in Rebels was definitely a point of reference, but it wasn’t what we were specifically looking to recreate.

Source: starwars.com

Kimura: Sorry for being blunt here, but I have to ask: Do you have the next part of this story drawn up?

Igarashi: Yes! We want to take the story to outer space in the next part. Lop sets out after the Imperials to find Ochō, who has fallen into darkness. Along the way I have her meeting up with the Rebellion and having strange encounters of her own (laughs). I’d also like to do a story about Lop’s species.

Kimura: Going after the comrade that has gone over to the darkness is kind of the opposite we see with Tam in Resistance and Crosshair in The Bad Batch. That sounds fascinating.

Igarashi: Ultimately I’d like to see the story come to a happy ending, with Lop finally catching up with Ochō and the two working out their differences. Do you have a sequel to Tatooine Rhapsody in mind?

Kimura: Give me a shout and we’ll throw on a live performance right away. The title might change each time though, like “Endor Rhapsody” or “Coruscant Rhapsody” (laughs). It’d be fun to do an “Imperial Rhapsody”, too.

Igarashi: An “Imperial Rhapsody” would definitely be intense. I can imagine those lightsabers being used as glowsticks (laughs).

Kimura: Thanks for the idea (laughs).

Igarashi: That’d probably drive a lot of people nuts (laughs).

Kimura: I think we should be allowed to get away with that on this short (laughs).

Igarashi: I was meaning to ask, but is the Hutt guitarist in Tatooine Rhapsody related to Jabba? Did he do something bad that would have Jabba send a bounty hunter after him?

Kimura: The backstory has him as Jabba’s nephew. Basically he has some kind of debt to Jabba.

Igarashi: Perhaps he borrowed some money from Jabba to start up the band?

Source: starwars.com

Kimura: Haha, we didn’t really have all the details of that back story fleshed out.

--Now that you both have your directorial debuts under your belts, do you have any concept or something you want to do for your next creation?

Kimura: I want to do something fun, perhaps something that is more in the entertainment vein. I’d like to move beyond the conventional Japanese anime style and explore a bunch of other artistic styles.

Igarashi: The entertainment angle is also something I had in mind. One thing I really like is the depiction of characters. There is the massive character culture within Japanese anime in manga. It feels like the characters are the ones who really pull the audience in, more so than the story. This is actually something we aimed to do with Lop & Ochō, putting the characters front and center. While I want to craft the edgy images that I enjoy, I also want to compose something entertaining that is really character driven.

Source: Animetimes.jp

--We’re definitely looking forward to what you guys have in store with your next creations! Thanks for taking the time for this chat session!

「闇を抱えて」:漫画「バガボンド」に窺えるより相応しいフォースとの付き合い方“Take hold of the darkness”: Insight from the manga Vagabond into a better way for approaching the Force

日本語を勉強し始めたころ、できるだけ日本語と多く触れ合うようにした。その一環として、漫画をたくさん読んで、少しずつ日本語に馴染んできた。最初に読んだ漫画の一つは井上雄彦氏の「バガボンド」であった。その原作は吉川英治の「宮本武蔵」である一方、この漫画は別の視点から宮本武蔵の若い頃を脚色して、剣術を極める道を歩む武蔵の葛藤と成長を描いていく。この十数年あまりで何回も読み返して、毎回いつも新たな発見が待っている。

One thing that I tried to do when I first started studying Japanese was to expose myself to the language as much as possible. I made it a point to read a lot of manga, and in doing so I steadily grew accustomed to the language. One of the first manga I read was Vagabond by Takehiko Inoue. It is based off the novel Miyamoto Musashi by Eiji Yoshikawa, but Inoue chooses to portray Musashi from a different angle, focusing on his struggles and growth in the younger years of his quest for mastery of the sword. I have revisited this manga countless times over the last 15 plus years, and each time brings new discoveries.

Source: Manga Vagabond

「バガボンド」の第一巻と第二巻では、天下分け目と言われる関ケ原の戦いの直後を描く。負けた西軍の足軽であった武蔵が追われる身となり、逃げ彷徨う中で数多くの人を殺して、死ばかりを目にしている内に生きる意義を見失われていく。「鬼」と追手に呼ばれる武蔵は、その延長で次第に自分の中の闇が拡大し、自分自身を呑み込まれる。そこで、どん詰まりとなった武蔵を追手の前に捕まえたのは沢庵という禅宗の宗呂。沢庵との出逢いによりある意味で武蔵が生まれ変わる。第二巻の終わりに沢庵が武蔵に向けて言い告げる言葉が印象に残る。そのシーンを下記の通り抜粋する。

The first two volumes of Vagabond take place right after the Battle of Sekigahara, the clash that effectively ensured Tokugawa Ieyasu would rule Japan. Musashi becomes a fugitive as he was an ashigaru (foot soldier) in the Western Army, the losing side. He kills scores of his pursuers as he runs for his life, and in the process he begins to lose that sense of purpose in living as a result of being constantly surrounded by death. His pursuers refer to him as an oni (demon, monster), and hearing that causes the darkness within Musashi to grow to the point that it engulfs him. Emotionally shattered, the man who succeeds in capturing Musashi is Takuan, a Zen priest. Musashi’s encounter with Takuan, in a certain respect, marks his own rebirth. The words Takuan says to Musashi at the end of Volume 2 really left an impression on me. Here is a quote from that scene:

「(沢庵) 今までのお前をも見捨てるのか?殺すのみの、修羅のごとき人生が本望か、武蔵(たけぞう*)? 違うよ。お前はそんなふうにはできていない。闇を知らぬ者に、光もまた無い。闇を抱えて生きろ、武蔵!やがて光も見えるぞ。」

*第3巻以降は「たけいぞう」を「むさし」に名前の読み方を改める。

“Are you just going to forsake the person you have been up until now? Is a life of carnage in which all you do is simply take life really what you want, Takezou*? No. You’re not made for that. Listen to me. Those who know not the darkness know not the light. Take hold of that darkness and live, Takezou. You will then see the light.”

*Takezou is the alternate reading for the same kanji characters that make up the name Musashi. He takes on the name Musashi from Volume 3.

Source: Manga Vagabond

光が物体を当たると、まるで延長線の如しその物体から陰が投影される。また、日や月が雲間に隠れると暗くなり、光の存在感が弱まる。光と陰、つまり光と闇は切り離さない共存である。それが良く表現されているのは「闇」との同様のルーツを持つ「暗」の字の成り立ちである。以前このブログで紹介したことのある「スターウォーズ:漢字の奥義」によると「暗」の成り立ちは下記の通り:「 " 暗 " は、太陽の形を示す " 日 "と、読みを表す" 音 "から成り、日が隠れて「くらい」という意味を示す。」要するに、漢字に置いて「暗」や「闇」の意味を成すため「光(日)」が欠かせない。その意味で、この漢字の意味と成り立ちを念頭に改めて沢庵の言葉を読み返すと、「闇(暗)」と「光(日)」の関係がより深淵になる。そして、スターウォーズの世界へ目を向けると、あの遥か彼方の銀河系を一つに束ねるフォースに対するより相応しい付き合い方と理解を窺えると拙僧が思う。

When light strikes an object, it casts a shadow that seems to be an extension of that object. Likewise, the presence of light, whether it be the moon or sun, is dulled whenever clouds pass over it. The existence of light and shadow, and therefore light and darkness, is intertwined. A wonderful representation of this is the formation of the kanji character 暗 (an, kurai), which shares the same roots as the character 闇 (yami). Both of these characters convey the idea of “darkness”. According to Star Wars: Kanji Story, a book I have previously highlighted on this blog, the character was put together in the following manner: “The kanji 暗 features 日, which depicts the figure of the sun, and 音, which influences the reading of the character. Combining these elements, it describes darkness as what happens when the sun is hidden behind the clouds.” In short, “light” is essential to defining the meaning of the two characters for “darkness” within the workings of the kanji character system of the written Japanese language. In that respect, the meaning and formation of these kanji characters make the relationship between light and dark all the more profound when we read that quote of Takuan’s again. Applying this to Star Wars, it is here that I believe we can see a more appropriate approach to and understanding of the Force, the energy field binding together that galaxy far, far away.

上記の沢庵の言葉の最後にもう一度見てみよう。「闇を抱えて生きろ、武蔵!やがて光も見えるぞ。」ここで「抱える」は「受け入れる」ではなく、「認める、肯定する」との意味合いが織り込められているではないかと思う。換言すれば、「闇を否定せず、自分の一部でもあると認めよう、武蔵」と沢庵が唱えている。その事実を認めることにより、光はやがって見えるようになるとのこと。沢庵が唱える光と闇の関係をフォースに照らし合わせてみると、旧共和国の晩期のジェダイ騎士団の破滅に繋がった根本的な誤解が浮き彫りになると拙僧が思う。それは「闇を認める=闇を受け入れる」との誤解である。その誤解のせいで、闇を積極的に否定することがジェダイ騎士団の独断的な信条と確定され、フォースの全体の在り様を見遮ってしまったとも言えよう。

Let’s take a look at the last part of Takuan’s message: “Take hold of that darkness and live, Takezou. You will then see the light.” The implied meaning of the Japanese word “抱える (kakaeru: to take hold of, to carry)” here is not so much “受け入れる (ukeireru: to accept, to welcome into one’s being)”, but rather more the idea of “認める、肯定する (mitomeru, kotei suru: to acknowledge, recognize)”. With this connotation in mind, we see that Takuan is telling Musashi not to deny the presence of the darkness, but rather accept that it is part of him. The recognition of this fact is what brings the light into view. When we take this the relationship between dark and light that Takuan espouses here and apply it to the Force, it brings to light a fundamental misunderstanding that played a part in the downfall of the Jedi Order in the final days as it existed in the final days of the Old Republic. The Order wrongly equated “acknowledging the darkness” with “accepting and embracing the darkness”. This misunderstanding led them to actively deny the presence of the darkness, a practice that crystallized into a dogmatic view that prevented them from seeing the Force in its entirety.

旧共和国の晩期のジェダイ騎士団と違って、黎明期のジェダイはフォースをより大局的に見ていた。その価値観が銀河系のあちこちで築かれた古代ジェダイの寺院のモザイクやほかのジェダイ美術に表現されている。「最後のジェダイ」ではルークが隠棲した惑星アクトには最初のジェダイの寺院があって、それは島の洞窟や岩片の特徴を利用される建築であった。その意味で日本の古神道に窺える「自然との共存」とスターウォーズにおける生きるフォースとの共和という共通点を視覚的に演出している。寺院の中には「ジェダイ・プライム」と呼ばれる最初のジェダイのモザイクを底としたプールがあった。「アート・オブ・スターウォーズ:最後のジェダイ」にそのモザイクのコンセプトアートと決定稿をこう解説する:

Unlike the Jedi Order in the latter days of the Old Republic, the Jedi at the dawn of the Order held a broader view of the Force. This take on the Force is evident in the mosaics and other Jedi art in the ancient Jedi temples scattered across the galaxy. Ahch To, the planet to which Luke exiled himself in The Last Jedi, was home to the first Jedi temple. The architecture of this temple made use of the natural features of the island’s caves and rocky enclaves. In that respect, it provides a visual depiction of the shared traits between the coexistence with nature seen in the old version of Shinto in Japan and the harmony with the living Force in Star Wars. Inside the temple on Ahch To was a pool with a mosaic of Jedi Prime, the first Jedi, at the bottom. The book Art of Star Wars: The Last Jedi (translated back into English from Japanese version) provides the following explanation about the concept art and final version of the mosaic created by Seth Engstrom:

“セス・エングストロムが手掛けたジェダイ寺院のデザインは、道教が用いる陰陽のシンボル(世界は闇と光のバランスで構成されており、両者の差は知覚によるものに過ぎないという思想の反映)を元にしている。ジョージ・ルカースも、「帝国の逆襲」を監督したアービン・カーシュナも、仏教の禅宗を参考にしてフォースを描写した。「これは最初のジェダイ、いわばジェダイ・プライムの姿を模したシンボルだ」エングストロムは2016年3月にそう説明した… 「それが左右に分かれてフォースの暗黒面と光明面に繋がっている。黒い石は宇宙の構造を保つフォースそのものだ。」”

“The Jedi Temple design conceived by Seth Engstrom was inspired by the Taoist imagery of the ying (陰) and yang (陽), which depicts the world as a balance of dark and light, with the difference between the two being no more than perception. George Lucas and Irvin Kershner, the director of Empire Strikes Back, both used Zen Buddhism as a base of reference in depicting the Force. ‘This is a representation of Prime Jedi, the first Jedi,’ said Engstrom in March 2016… ‘both sides of the Force are connected, with the light on the left and dark on the right. The black stones are the Force binding the galaxy together.’ ”

Source: The Art of the Last Jedi

しかし、数千代に渡ってジェダイ騎士団が暗黒面を否定するようになってきた。その象徴の一つは惑星コルサントにあったジェダイ寺院でもある。その寺院は古代のシス神殿の跡の上に建てられていて、当時のジェダイたちはその神殿に宿った暗黒面の力が完全に消され、若しくは封印されていたと信じていた。この寺院は、ジェダイ騎士団が数千代に渡って暗黒面の存在を封印し、否定し続けてきた歴史を物語る。皮肉にも、これは暗黒面に対する「恐れ」の表れでもあり、その恐れに基づいてジェダイが否定的な捉え方をとった。そして、否定すればするほど、暗黒面たる怪物がどんどん大きくなっていく。

However, over the course of thousands of generations, the Jedi Order came to deny the Dark Side of the Force. One symbol of this denial was the Jedi Temple that was on the planet of Coruscant. The temple itself was built on the ruins of an ancient Sith shrine, with the Jedi of that era believing that the Dark Side presence which dwelt there had been effectively removed or sealed away. It is a testament to the history of a Jedi Order that sought to entomb the Dark Side and deny its presence. Ironically, this negative view the Jedi held was born out of fear, a fear of the Dark Side. Likewise, the more the Jedi sought to deny the existence of the Dark Side, the larger that monster grew.

では、フォースの暗黒面とどのようにお付き合いすればいいかが問われる。その答えは案外に簡単であるとクローンウォーズの終幕でヨーダが悟る。死後もフォースの流れに置いて自我を保つ術があるとフォースの霊体となったクワイ=ガン・ジンから教えてもらったヨーダは、フォースの惑星へ出向いて、その術を知るフォースの女官たちを探し出す。フォースの女官は五人の妖精である組になっていて、一人ずつはフォースの一面を表している:平静、怒り、悲しみ、困惑、喜び。この女官の構成を検証してみると、窺えてくるのはフォースのバランスである。喜びは明確に光明面と所属するに対して、怒りはまた明確に暗黒面に所属する。残りの三つ(平静、悲しみ、困惑)はどの面に所属するかははっきりしない。フォースを成り立つにはその一つずつの面が不可欠であり、一つがないとバランスが相成らない。また、フォースは常にこの五つの面を移ろい行く存在でもある。

The question then is how does one approach the Dark Side. The answer for that is surprisingly simple, as Master Yoda discovers towards the end of the Clone Wars. He learns from the Force ghost of Qui Gon Jin that it is possible for one to preserve their essence in the Force even after death, and thus sets out to the Force planet to find the Force Priestesses who know this is done. There are a total of five Priestesses, and each of them represents an aspect of the Force: Serenity, Joy, Anger, Confusion, and Sadness. When we take a closer look at the composition of this group, we discover that they are the balance of the Force. Joy is clearly a trait of the Light Side, while anger falls under the Dark. However, it is not readily clear as to which side the remaining three (serenity, confusion, sadness) belong. Each of them is essential in the composition of the Force, and the absence of any single one throws the Force out of balance. Likewise, the Force is continually transitioning between these five elements.

Source: The Clone Wars (Lucasfilm)

ヨーダがフォースの女官と出会うエピソードの最初にこの言葉が流れる:「恐れているものと向き合えば、己を解放できる」。フォースの女官たちから授けられた教訓はまさにその通りであった。それは自分の中に宿る闇と向き合って、認めることでした。でも、最初はヨーダが自分の中に潜むダークサイドの存在を否定しようとした。遠い昔にもう克服したと傲慢してしまったからだ。ただし、フォースの女官達に案内された洞窟の中へ入ると、不吉な笑い声が響き渡る。それはヨーダ自身のダークサイドであり、洞窟の壁に投影される陰から現れる。そして、ヨーダを襲い掛かる。激闘の中で二人の間に交わされる会話は下記の通り:

The following quote appears at the beginning of the episode in which Yoda meets the Force Priestesses: “Facing all that you fear will free you from yourself.” That is precisely the nature of the trial that the Force Priestesses had in store for Yoda. In short, he had to face the darkness within himself and acknowledge it. At first Yoda attempts to deny that darkness within him exists, for in his hubris he believes that he had vanquished it long ago. However, when he enters the cave to which the Force Priestesses led him, he hears an ominous laugh echo throughout the chamber. That voice is none other than his Dark Side presence, and it emerges from the shadow cast on the wall of the cave. Here’s the exchange the two have during their bitter contest:

暗黒面のヨーダ: 「ヨーダは俺が憎い。ヨーダは俺ともう遊んでくれない。俺を役立たずと思っている。」

Dark Side Yoda: “Yoda hates me. Yoda plays not with me any more. Yoda thinks I’m not worthy.”

光明面のヨーダ:「お前など知らぬ」

Light Side Yoda: “Yoda recognizes you not.”

暗黒面のヨーダ:「自分の中にあるものを見ないのか?”

Dark Side Yoda: “Yoda see not what’s inside Yoda?”

光明面のヨーダ:「その手に乗るものか?」

Light Side Yoda: “I choose not to give you power.”

暗黒面のヨーダ:「その空しさが俺を育てている、戦争で退廃した日々を過ごしているくせに。本当の自分を知るのだ。俺と向き合え、でないと食い尽くすぞ。」

Dark Side Yoda: “And yet you spend your days in the decadence of war, and with that I grow inside of you. Know your true self. Face me now, or I will devour you!”

光明面のヨーダ:「わしの一部ではない。

Light Side Yoda: “Part of me, you are not.”

暗黒面のヨーダ:「俺はお前の一部だ。生きるものすべての中にいる。力を与えてるのになぜ憎む?」

Dark Side Yoda: “Part of you, I am. Part of all that lives. Why do you hate that which gives you power!?

「俺を役立たずと思っている。」

“Yoda thinks me not worthy.”

光明面のヨーダ:「お前の正体が分かった。お前は確かにわしの一部。だがわしを支配できん。忍耐と訓練によってお前を支配する。お前にはわしを支配できん。お前はわしの暗黒面だ。受け入れん。」

Light Side Yoda: “Recognize you I do. Part of me you are, but power over me, you have not. Through patience and training, it is I who control you. Control over me, you have not. My Dark Side you are. Reject you, I do.”

ここで、ヨーダがまた自分に宿る闇の存在を否定しようとする。自分のダークサイドに向けて「お前など知らぬ」や「わしの一部ではない」と言い捨てる。でも、否定すればするほどダークサイドが攻撃的になり、ヨーダをその存在に向き合いさせようとする。ヨーダの発言と闇に対する態度はジェダイ騎士団全体の闇に対するスタンスそのものと見捉えることも出来る。そして、ヨーダを始め、ジェダイ騎士団はクローンウォーズにおいて戦争で退廃した日々を過ごしていたあげく、闇が形となった傲慢が育まれた。

Here, we once again see Yoda attempt to deny the darkness that is within him. He flat out tells his Dark Side self that “Yoda recognizes you not” and “part of me, you are not.” However, with each rejection his Dark Side self grows more aggressive, compelling Yoda to face him. Yoda’s words and stance toward his Dark Side self can be taken as the entire Jedi Order’s stance toward the darkness. And like Yoda, the entire Jedi Order in the Clone Wars spent their days in the decadence of war, which in turn allowed the Dark Side to grow and manifest itself as their hubris.

ここでもう一度沢庵の言葉に戻りたい:「闇を抱えて生きろ」。大辞典によると「抱える」にはこの意味もある: 「自分の負担になるものをもつ。厄介なもの、世話をしなければならないものを自分の身に引き受ける。」自分のダークサイドとの激闘の末、その闇に対する責任を認めるヨーダ。ダークサイドは確かに厄介なものであり、それと向き合えるのは難しい。一方、ジェダイはフォース使いである上、フォースに対する責任を全うしなければならない。自分に宿る闇を認めるのはその一環である。沢庵の言葉が仄めかすように、フォース使いなるものは光だけではく、闇も抱えて生きる道も歩む。ただし、闇を否定してしまうと、それが傲慢という怪物を生み出し、気づかないうちにその傲慢に支配されていく。これはまさにジェダイ騎士団に訪れた不幸な終焉でもあった。この厳しい教訓を経たヨーダは、傲慢として具現された闇を自分のものにし、支配することが出来た。つまり、「恐れているものと向き合えば、己を解放できる」というゴールを達成できた。ジェダイ騎士団にとってもうはや手遅れでもあったけど、その教訓をしっかりと新たなる希望たる者に継がせることが出来た。そして、それによりジェダイの再起の礎を敷いた。