日本の中空構造 Japan’s Functional Emptiness

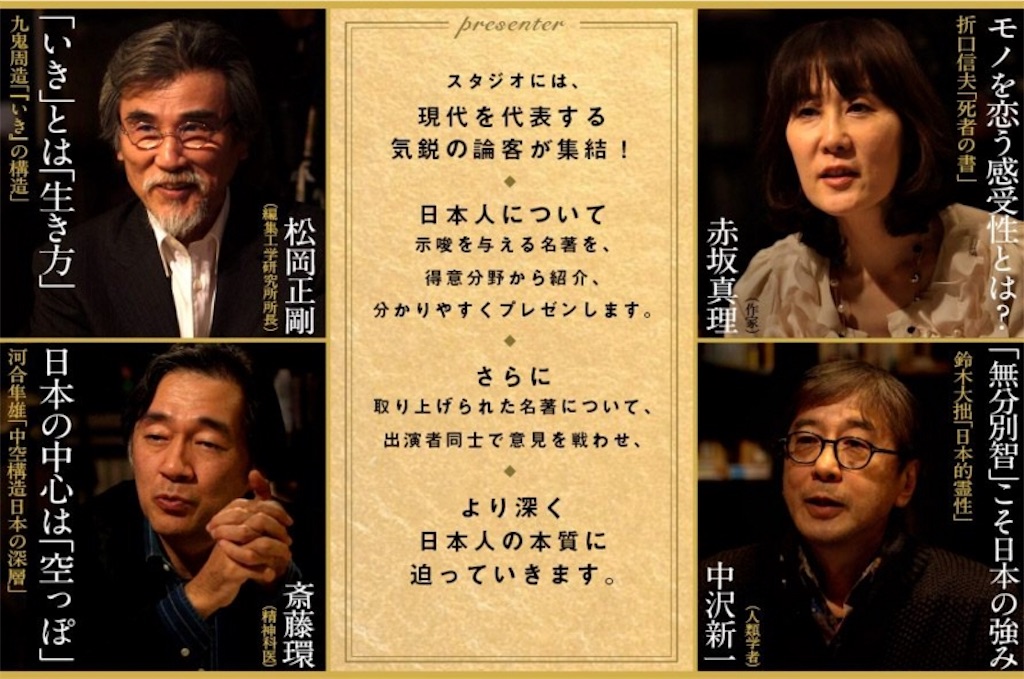

日本のテレビの気に入り番組を挙げようと言われますと、まず思い浮かぶのはNHKで放送される「100分で名著」です。「旧約聖書」から「般若心経」まで、多岐に渡る名著を取り上げて、四回(一回ずつは25分)に渡ってその名著のテーマと文化的な価値を考察する構造となっている番組です。ちょうど三年前の正月にこの番組のスペシャルバージョンである「100分de日本人論」が放送されて、非常に興味深い座談会となりました。この座談会に参加したのは現代日本を代表する下記の4人の論客:

If I was asked to name a particular Japanese TV program that I enjoy, the first one that comes to mind is “Master Works in 100 Minutes” on NHK. The show takes famous pieces of literature, ranging from works as diverse as the Old Testament and the Heart Sutra, and then examines their cultural importance over the course of four 25 minute episodes. Three years ago NHK aired a special edition of this program during the New Year’s Holiday. Dubbed “Japanese Theory in 100 Minutes”, this fascinating panel discussion brought together four of Japan’s leading scholars today:

Source: NHK

松岡正剛(編集工学研究所所長)

赤坂真理(作家)

中沢新一(人類学者)

Seigo Matsuoka (Head of Editorial Engineering Laboratory)

Tamaki Saito (Psychologist)

Mari Akasaka (Novelist)

Shinichi Nakasawa (Anthropologist)

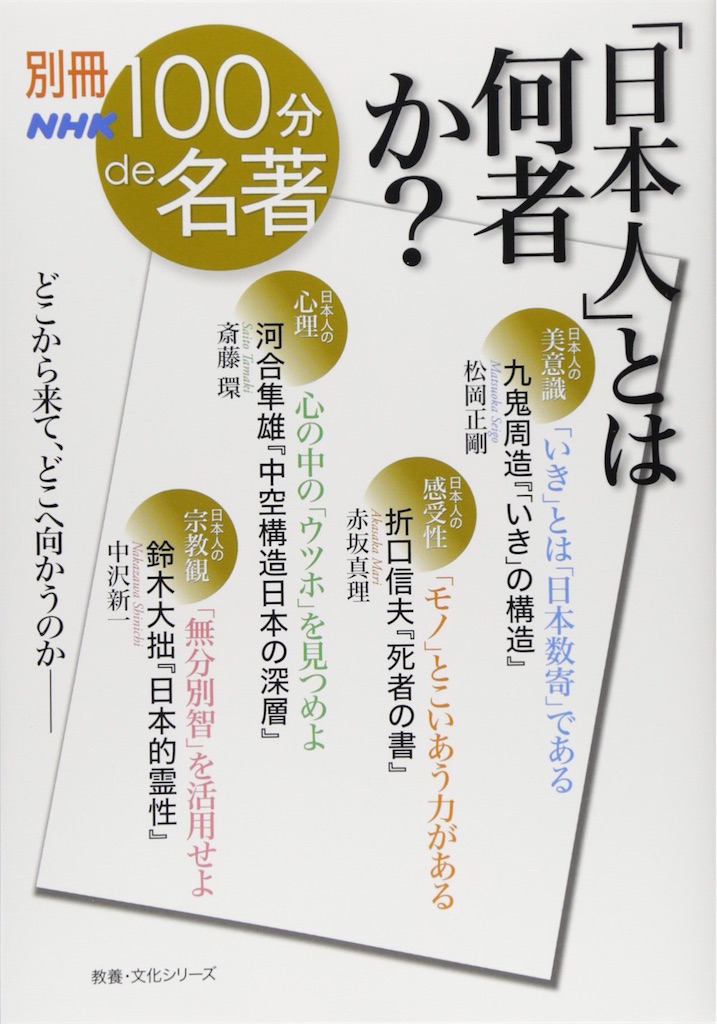

この四人が日本人の本質をよく表していると考える一冊を紹介し、分かりやすく解説するという特別企画でした。あまりにも深い話でもありましたので、座談会の内容をそのまま書き起こした出版物にもされました(購入済み)。

Each member of this panel discussion was asked to introduce and provide a straightforward explanation of one work they felt conveyed a unique Japanese quality. The conversation was incredibly deep, so much so that NHK decided to publish a volume that compiled everything the panelists said over the course of the discussion (a book which I have bought).

Getting to the Core of Being Japanese

このブログではこの座談会で紹介された本を一つずつ取り上げたいですが、まずこの投稿で考察するのは斎藤環が選んで紹介した河合隼雄(かわいはやお)の「中空構造日本の深層」の単著です。この本は「日本文化の中心は、空っぽなのだ」という長年の研究において河合氏が辿り着いた独特な持論が展開されます。

I’d love to examine each of the books discussed by this panel, but for the sake of this post I will take a look at the book introduced by Tamaki Saito: Getting to the Heart of Japan’s Empty Framework by Hayao Kawai. This book lays out the original theory that Kawai arrived at after many years of research. He argues that the core of Japanese culture is in essence “empty space”.

日本の神話には、正体不明の謎の神様というのが、必ず出てくると共通点に河合氏が注目を当てました。「それぞれの三神は日本神話体系のなかで画期的な時点に出現しており、その中心に無為の神を持つという、一貫した構造をもっていることがわかる。これは筆者(河合)が “古事記”神話における中空性と呼び、日本の神話の構造の最も基本的事実であると考えるのである。」

One common feature present throughout Japanese mythology that Kawai zooms in on is the presence of an obscure divinity. “In Japanese myths, we always see three divinities appear at key moments within the narrative. The central figure of these trinities is always an idle divinity that does nothing. I (Kawai) refer to this as the “emptiness” of the Kojiki lore, and it represents the most fundamental truth within all Japanese legends.”

Source: NHK

河合氏が取り上げる典型の例は古事記の冒頭に登場する三人の神:アメノミナカヌシ (天之御中主)、ツクヨミ (月読)、とホスセリ (火須勢理)。アメノミナカヌシとホスセリ (火須勢理)はちゃんと有為な神として扱われている一方、ツクヨミは何もしないです。河合氏がこの神話の構造をこう説明します:「日本神話の中心は空であり、無である。このことはそれ以後発展してきた日本人の思想、宗教、社会構造のプロトタイプとなっていると考えられる。」

In his book, Kawai calls attention to three divinities that appear at the beginning of The Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters): Amenominakanushi, Tsukuyomi, and Hoseseri. While Amenominakanushi and Hoseseri are depicted as active players in the narrative, Tsukuyomi does absolutely nothing. Kawai explains this mythological structure as follows: “The very core of Japanese myths is empty, indeed nothingness. This structure provided the prototype for the underlying make-up of all Japanese thought, religion, and society that have developed from that point (ancient times) forward.”

Source: NHK

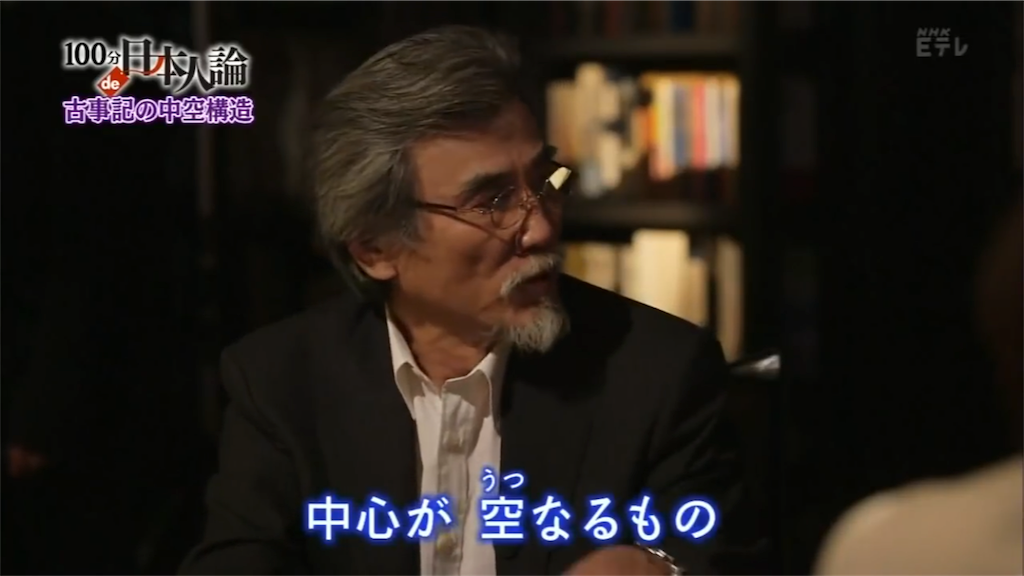

この点について座談会の話が弾み出します。まず松岡氏が注目するのは「中心は空(うつ)である」である点です。以前この松岡氏が唱える「現(ウツツ)」が派生させる「移ろい」というコンセプトを考察する記事を書いたこともありますが、ここで松岡氏が同様のコンセプトが河合の唱える中空構造の仮説に置いて働いていると下記の通り解説します(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

This point really gets the discussion moving. Matsuoka’s draws attention to the “empty core” concept and states how the “空 (kuu, void or sky)” character in the word “中空 (chuukuu)” can also be read as “utsu.” This reading is derived from that of the character “現 (utsutsu, the now)”, which in turn gives rise to the idea of “移ろい (utsuroi, change or transition)”. I have explored this idea in a previous post, so check it out if you would like to learn more. As shown below, Matsuoka argues that this same concept is at work within Kawai’s “empty core” hypothesis (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

“中心に「ウツなるもの」を置き、それがあることによって両脇の二つが動いているという河合の仮説には納得のいくものがあります。一見空っぽだが、いざとなるとそこに何かが湧き出てきたり、力が潜んでいたりする。信号に青と赤のほかに黄色があるように、A/非Aという二尺せず、真ん中に三つ目を置くことによって、どちらも生かすのです。日本人は中空構造に無意識であるかゆえなのか、方法的なことをかなり特別に意識し、大切にしていると思います。そうしないと中空に異質なものが入ってきたときに、大変な事態になりかねない。”

“I believe there is some weight behind Kawai’s proposition of a three-part structure centered on something empty, but with that void putting the two sides into motion. At a glance it appears there is nothing but emptiness, but out of necessity this void can give rise to something, or transform into this well of latent power. A stoplight has not just red and green, but also yellow. It’s more than just A or not A; putting something in the middle allows us to keep both. Japanese people pay special attention to the processes behind things, perhaps because of this functional emptiness at work within their subconscious, and really cherish them. They have to clue in on these processes, for failure to do so can cause things to fall apart when something alien enters that void.”

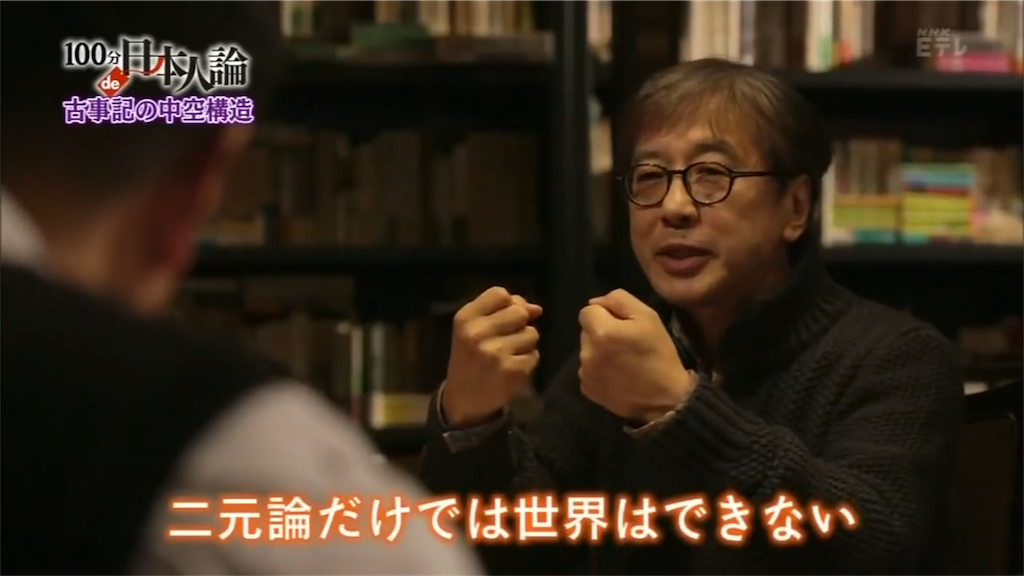

中沢氏が松岡氏のいうこの中間の特徴が日本の社会や自然に対する価値観においてどのように機能しているか、そしてどのような危険性が潜んでいるのかを下記の通りの解説を付け加えます(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

Nakazawa further elaborates on this idea of putting something in the middle that Matsuoka described. In the following excerpt, he shows how this idea works within Japanese society and its view on nature, as well as the potential danger it entails (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

Source: NHK

“宇宙を作るには三項が必要だが、三項目は潜在的で表へ出ない。日本の神話において、天と地、海と山という二元論の起源はバーチャルで、このバーチャルに一項が与えられている、というのが河合さんの基本的な直観なのではないでしょうか。人間は、自然な状態だとこの思考方法が一番合理的で、例えば中空領域を置くことで、お互い妥協を図ることができます。自分と違うものを排除するのではなく、相手の原理を自分の中に入れることが可能になってくる。”

“You need three elements to form the cosmos, but the third is this latent force that never comes to the forefront. In my view, Kawai’s basic hunch is that an extra element is added to the virtual base underlying the dualistic facets of Japanese legends, such as the pairings of earth and sky or sea and mountain. This is the most logical mode of thought for human beings in our most natural element. In allotting this empty space, we create an area where we can work things out and reach a compromise with one another. Rather than simply eliminating what is different from you, it becomes possible to take the tenets of the “other” and make them a part of your being.”

“その例として典型的なのが、日本の風景は、中間領域を残しておくことが基本になっています。人間と、山の生き物。二つが重なり合うところに里山を作る。里山は中間領域ですから、人間にとっても、昆虫や魚、動物にとっても素晴らしい住処(すみか)にも成り得る。生き物の要求する生存条件を認めているわけです。計算や計画といった合理性で出来上がった世界には、中間がありません。ところが日本人の社会は中間性というものをベースにできていますので、その点は人類の期待、希望の星でもあります。しかしそのことに無自覚のままだと、70前の戦争と同じような状況に突入してしまう可能性もあるという、両刃(もろは)の剣でもあるのです。”

“Japanese landscapes provide us with great examples of this principle at work, for they are based on the idea of leaving some form of middle ground. This is the satoyama (里sato for “village” and 山yama for “mountain”) concept, or the idea of a place where human beings and life on the mountain come together. A satoyama holds the potential to be a truly wonderful place for all life—human beings, insects, fish, and animals—precisely because it is a middle ground. It’s an acknowledgement of all the conditions for subsistence that living things seek. On the other hand, there is no middle ground in a world rooted in the rationality of calculation and planning. In a certain respect, Japanese society stands as a beacon of hope for people of all humanity because it is based on this idea of allowing for room in the middle. That said, this very characteristic is a two-edged sword. If we are completely oblivious to this, we could fall headlong into the same set of circumstances as that war 70 years ago.”

そこから赤坂氏がその三項構造の考察を下記の通り続きます。中沢氏と同のようにこの三項構造は人間にとって一番自然な思考法と主張しつつ、過去に日本人がその構造に無自覚になるとどの悲惨を招いてしまうかを指摘します(「日本人とは何者か?」より引用)。

Akasaka continues this examination of the three-part structure at work. Just like Nakazawa, she believes this is the most natural mode of thought for human beings. At the same time, she also draws attention to Japan’s past and the tragic consequences of becoming oblivious to this structure (quote from Getting to the Core of Being Japanese).

Source: NHK

“日本人は「神」がわからない、世界で例外的な民族である」などというふうに、日本人自身の間でも、言われます。が、私は、この場合に「神」と言われている一神教の神という概念(そして善悪二元構造)は、危機の時代の思考の飛躍から生まれたものであって、人間の自然状態では「三項構造」を出してくるのではないかと思っています。この点は、中沢新一先生に確認しましたが、そうだということでした。”

“There are those who say—including some Japanese people—the fact we don’t understand “God” makes us one of the world’s unusual races. The God I’m referring to in this instance is of the monotheistic religious tradition based on a dualistic structure of good and evil. I’ve always held that this form of religion bursts forth from the intellectual currents of ages of crisis, and that the natural mode of thought for human beings is more aligned with a three part structure. Indeed, Professor Nakazawa has reaffirmed that is the case.”

“日本人が近現代まで、三項構造でやってこられたのなら、それは幸せなことだとも言えると思います。その三項構造の思考パターンを無意識に下敷きにして、天皇を神であり中心とした国を、明治(時代)に作りました。それはまさに天皇を「責任があって、責任がない立場」、つまり「三項構造の真ん中」のように中空構造につくるやり方でした。それは良い悪いではなく、ただの「構造」です。けれど、ただの構造であるからこそ、それが「利用」されるとき、誰にも止められず、誰の責任も問えない悲惨が発生します。それは入力したものが自動的に達成されるブラックボックスのようです。そして、そのことがうまく説明できなかったために、日本人は戦後、戦争のことについて口をつぐむことになりました。そして語れないひずみも、現在進行形でたまる一方です。あれほどの失敗は、まさに構造から来ていたと思います。そして、構造を用いるのにあまりに無自覚であったことから、来ていたと思います。その意味で思想的な「危機の時代」は、今も続いています。”

“Perhaps this three-part structure is what enabled Japanese people to endure into modernity. In that regard, I guess we could say we were blessed. In the Meiji era (1868-1912), Japan created a nation state with the Emperor as the divine head in the center, a system unwittingly based on that very three-part structure mode of thought. This approach led to the creation of a system that placed the Emperor in a position of “both responsibility and no responsibility.” It was a reflection of this empty core concept. This is not a question of good or bad; in the end it is just a system. However, when this system is “used,” it can court disasters that no one can stop or take the blame for. It’s like this black box that automatically carries out whatever is put inside it. Japanese people were unable to effectively explain the nature of this system after the war, and this failure has caused us to remain silent on the issue. The strain wrought by this silence continues to pile up today. I believe the system is root of that grave mistake of the past. Indeed, the fact we were so oblivious to this system being used is what led to that mistake. In that sense, we still find ourselves in an intellectual ‘age of crisis’.”

Source: NHK

上記の三人が話したように、河合氏が唱える中空構造は柔軟性に長けた思考方法でありながら、一長一短もあり、それを自覚して上手くコントロールする必要があると斎藤氏が論じます。一方、外来のものというレッテルを張ったまま共存していくという長所があります。漢字はまさにその象徴です。「漢の字」が示すように、中国の字でもありながら、日本語に当てはまって1500年以上に使い続けられています。また、中空構造によって日本文化的なものを並行して温存されていくメリットもあります。かつての神仏習合はその典型的な例でしょう。朝鮮半島を通して日本に入ってきた大陸の宗教である仏教が道を排除することなく、妙な形で習合し、それぞれの宗教が欠ける点を補い合う日本の風土に適した独特な宗教の構造を醸し出しました。

Just as these three scholars explained, the empty-core structure described by Kawai is an incredible flexible method of thought. However, it is not without its faults. Saito argues that the important thing is to recognize both its merits and faults, and work to effectively manage them. One advantage of this system is that it incorporates elements from the outside, finds a way to make them coexist, yet also retain a vestige of their roots. We see this exemplified by the use of kanji in Japan. The very characters used to form the word 漢字 (kanji) make it clear where their roots lie. 漢 represents kan or han, which implies Chinese, and 字 for ji indicates written characters. While they were adapted to Japanese language and have been in use for over 1500 years, they’ve never lost that foreign label. Another merit of the empty-core structure is that it finds a way to preserve Japanese elements alongside those that enter from the outside. A classic example of this is 神仏習合 (shinbutsu-shuugo), or the fusion of Buddhism and Shinto. Buddhism entered Japan via the Korean peninsula. Instead of eliminating Shinto, Japan found a singular way to meld this continental religion with its own native beliefs, cultivating a unique system in which each religion made up for what the other lacked.

他方では、中空構造に潜む危険性に対して河合氏が警鐘を鳴らしたと斎藤氏が言います。その中心が空であることは、一面極めて不安であり、何かを中心に置きたくなるのも人間の心理傾向であると言えます。上記の赤坂氏の話でその傾向が招いた悲惨も触れました。河合氏も次の警告を残しました。「今度中心への侵入を許した場合、日本の中空構造はもはや機能しないのではないか。」河合氏の言葉を念頭に、日本人は全存在をかけた生き方から生み出されてきたものを、明確に把握してゆこうとしなければならいのはこの四人が至った結論です。これからの日本はこの教訓をどのように活かせるのかを拙僧も見守っていきたいと思います。

On the other hand, Saito shows how Kawai also warned of the danger inherent in this empty-core structure. The fact that there is nothing in the middle gives rise to a highly unstable quality. When faced with such instability, Kawai claims that human nature makes us want to put something in this middle ground. As we saw earlier, Akasaka touched upon the grave outcome of this tendency. Kawai leaves the following warning in his book: “The next time we let something encroach upon this middle space, Japan’s empty-core may very well cease to function.” With these words in mind, the four scholars concluded that the key is for all Japanese people to maintain a clear awareness of this structure, born of the living modus created over their entire existence. As we head into the future, I intend to see how Japan applies this lesson.

筆者の撮影

Author photo